Painter Helen Frankenthaler gives us an art history lesson, 60 years later

Filling a 1965 Helen Frankenthaler ARTFORUM interview with links and photographs for you to explore!

❥ This email may be truncated in your inbox. To make sure you are reading the entire post, please move yourself along to a web browser!

More from me + Absolument can be found in these places:

Website | Instagram | Shop Absolument | Book Recs - Merci, thank you tons and tons for reading!

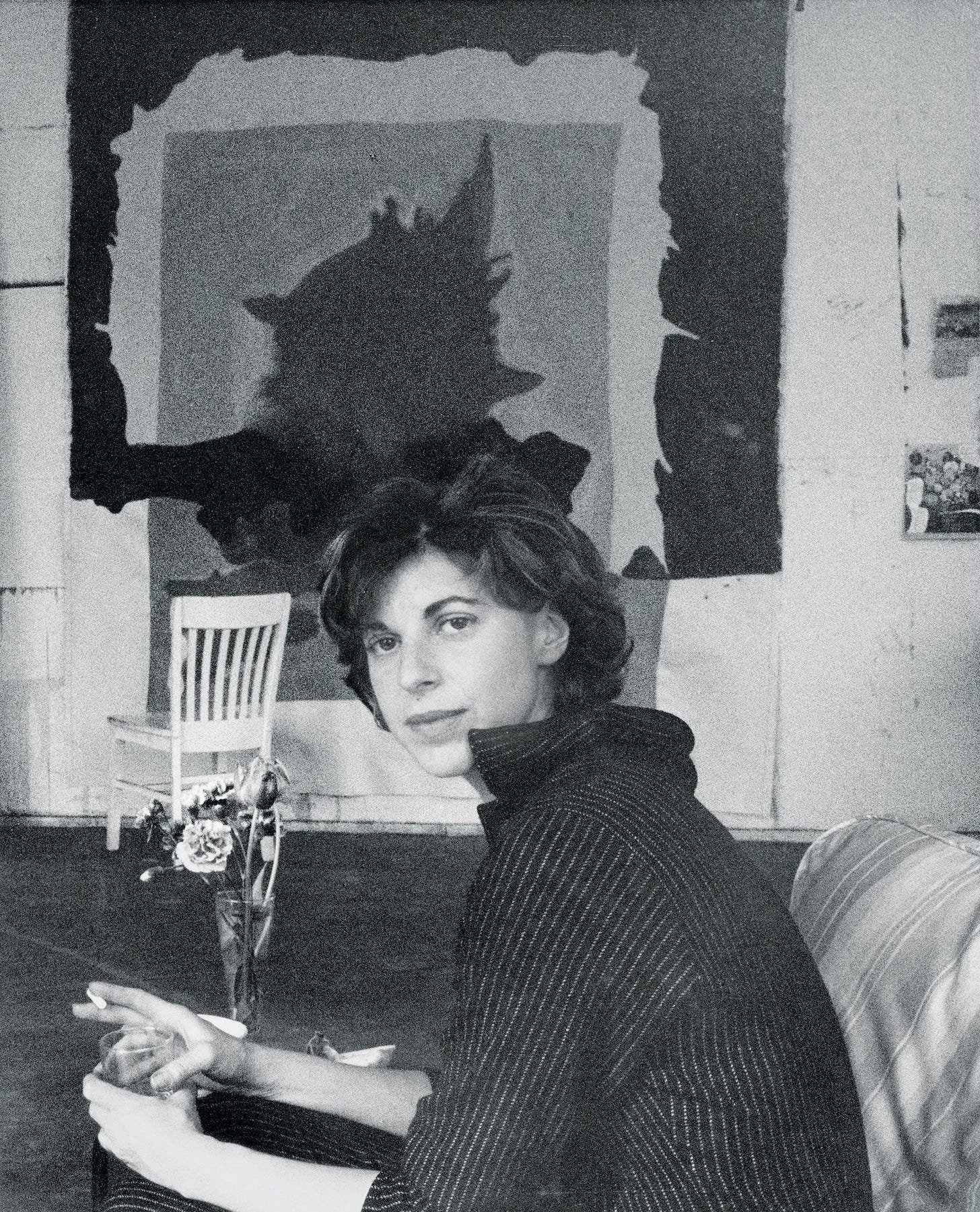

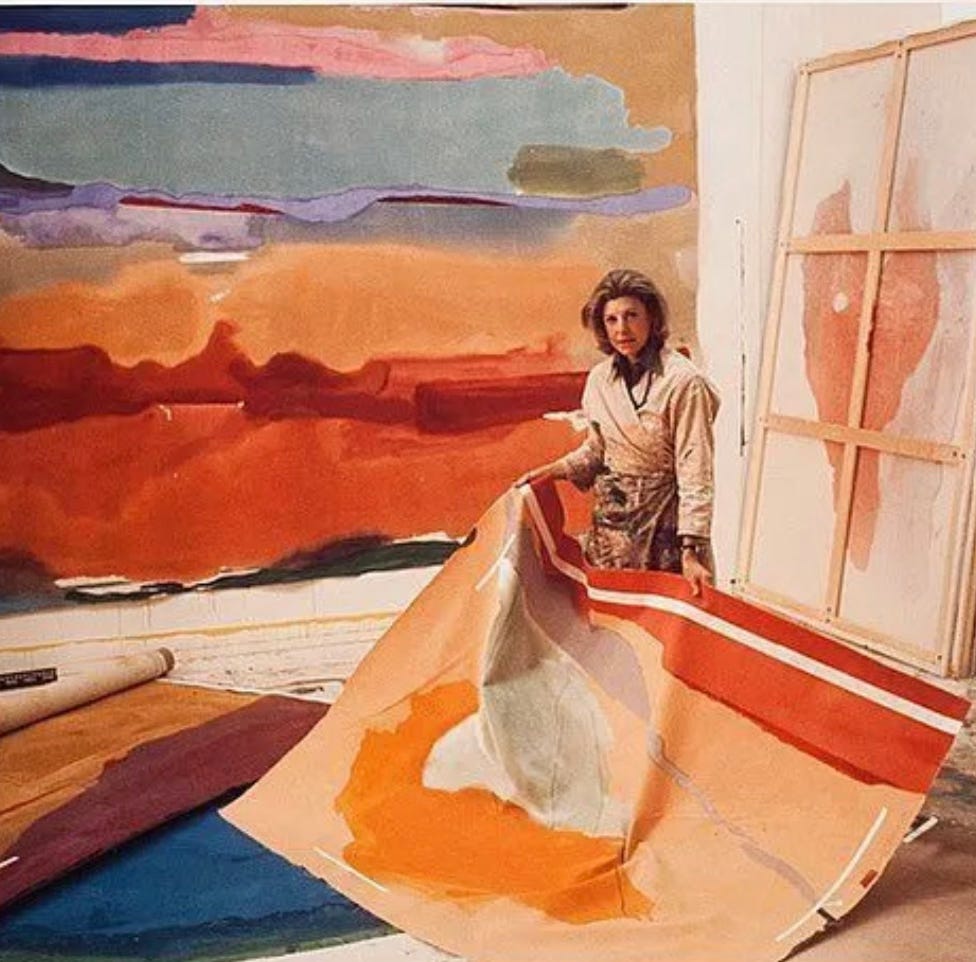

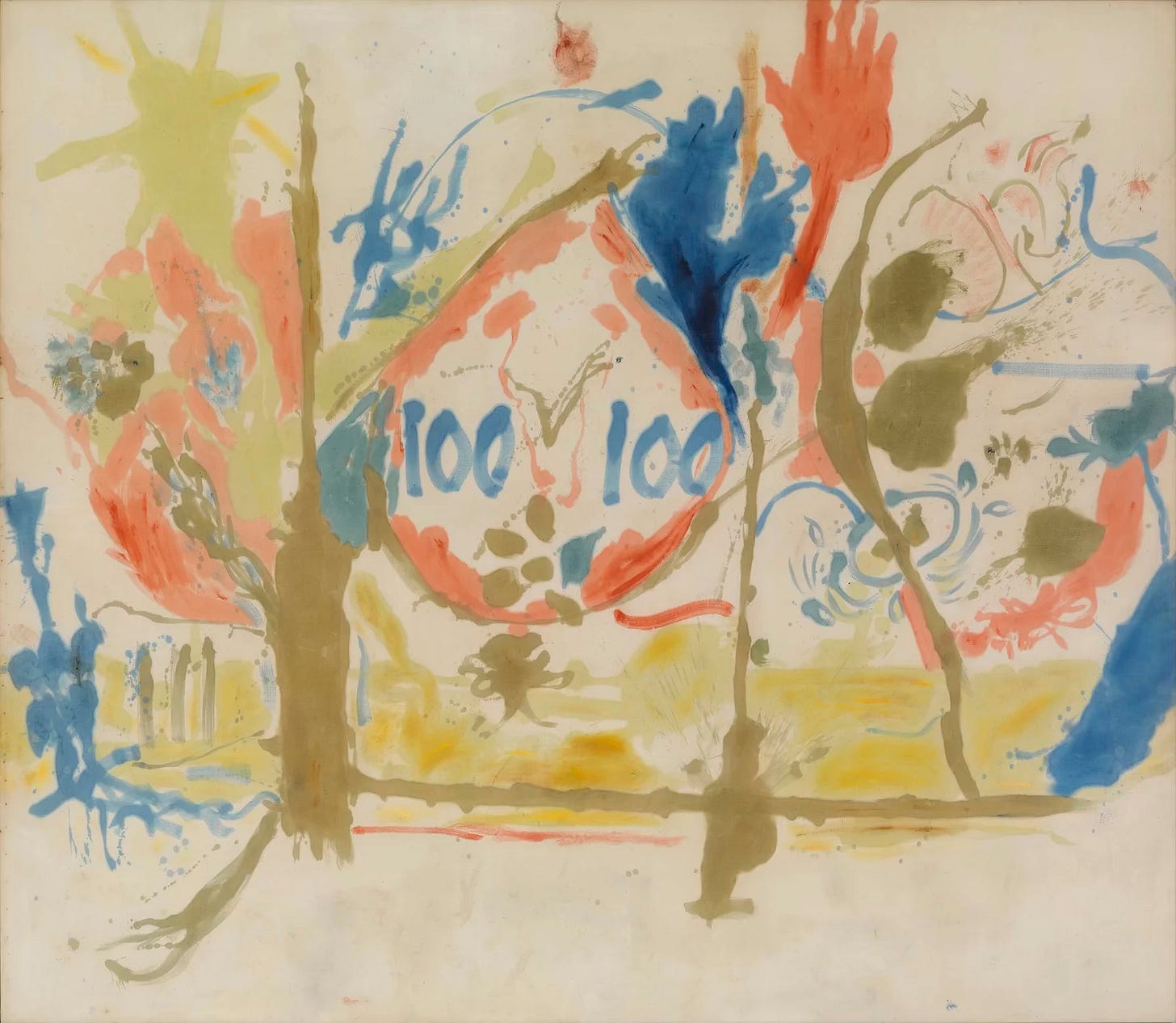

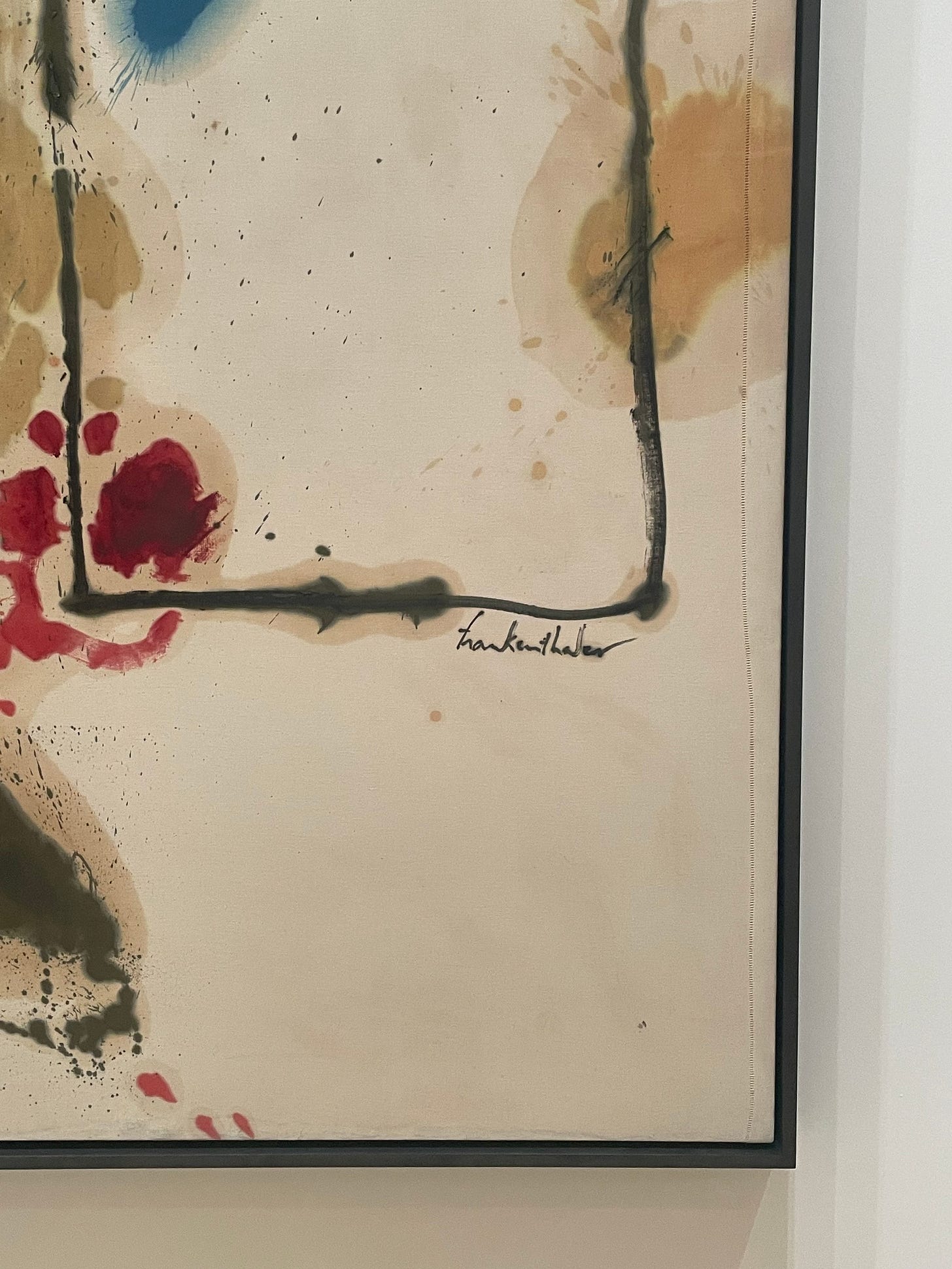

Sometimes I’ll read an artist interview that absolutely steals the breath from me. Usually, these are text-dense and even though they are referring to art, they don’t have nearly enough photographs attached to them! This interview of Abstract Expressionist painter Helen Frankenthaler was published in ARTFORUM’s October 1965 issue. It included only four photographs of Frankenthaler paintings, but compared to the richness of her storytelling, it doesn’t quite feel like enough. So, I’m taking it upon myself to illustrate her words!

You know when a director provides commentary alongside a film they’ve created? Think of this post as something similar to that, but instead, my purpose here is to give you some extra exploration room and visuals to make Helen’s words even shinier. You’ll find that I’ve hyperlinked a ton of her words, hoping that you’ll follow the tracks to other art stories. I’ve also added some color photographs of the artwork and people she refers to with care. What follows is a Franthenthaler-lead art history lesson. ❥

*All text displayed below is not my own—it belongs to Helen Frankenthaler, Henry Geldzahler, and ARTFORUM. Every image has been properly cited, too.

The interview with Helen!

How did you first get into painting?

When I was fifteen I started going to the Museum [of Modern Art] and a couple of galleries, mostly because of Tamayo, because he was teaching at my high school, Dalton. He was my first friend who was a painter. The first gallery I went into was the one in which he showed (Valentine Dudensing gallery).

In my early teens, it was my sister Marge who took me around the Museum; she took me to see Dali’s melting watches. It was the first time I really looked and I was astonished.

By the time I got to Bennington (March, 1946), I was quite involved in painting because of Tamayo. I had stayed in New York a term after high school—I was sixteen—I stayed in New York to paint with Tamayo. He taught me how to paint—Tamayos. He taught me how to stretch a canvas, mix mediums. I still have my pictures in his colors, blues, ochres, watermelon reds. I didn’t know he derived from Picasso. He thought I was a good student—and I made such good Tamayos!

Before Dalton I went to Brearley, as academic as Dalton was progressive. I painted academic still lifes, arranged twigs and flowers, wine bottles, eggs on white tablecloths. I loved painting those still lifes as realistically as I could—was good at it.

Once out of the Tamayo atmosphere I dropped the style. What I was more involved in at first at Bennington was painting the way I had at Brearley, very academic still lifes, or slightly Impressionist ones. I still, occasionally, when I get in a certain type of painting crisis, go back to drawing landscapes or an “accurate” portrait, but lately I tend to sit in the crisis rather than go back to drawing. Last summer I did a landscape out the window of Provincetown Bay, a scene I’ve painted many times before.

In 1952 on a trip to Nova Scotia I did landscapes with folding easel equipment. I came back and did the Mountains and Sea painting and I know the landscapes were in my arm as I did it.

At Bennington, the term I got there, Paul Feeley had just come back, after the war. I’d say his involvement then was with American-style Cubism; not so much Villon and Feininger as Max Weber. But he had a great eye; a marvelous teacher with a passionate curiosity about painting.

[Feeley’s] interest in Cubism encouraged me and that was my concern for three and a half years until I graduated. I could “do” a Braque still life—I’m not being presumptuous—I don’t mean I did a Braque still life, but I got—felt emotionally and intellectually—the style thoroughly.

There was also a seminar at Bennington with Feeley, with reproductions on the wall of Matisse’s Blue Window, a Picasso Banjo Player, a classic, simple Mondrian, Cézanne’s Card Players. We would discuss, dissect, ape them as you only can when you’re that excited. The exchanges were often thrilling, moving.

What did you look at that was totally abstract?

Total abstraction was something intellectual to me. I didn’t feel it; I could talk about a Mondrian but it didn’t occur to me to do it. I saw a Dubuffet show at Pierre Matisse in the late forties and came back with a catalog to Bennington. There were a lot of jokes but it was very compelling, a shot in the arm, a new vocabulary.

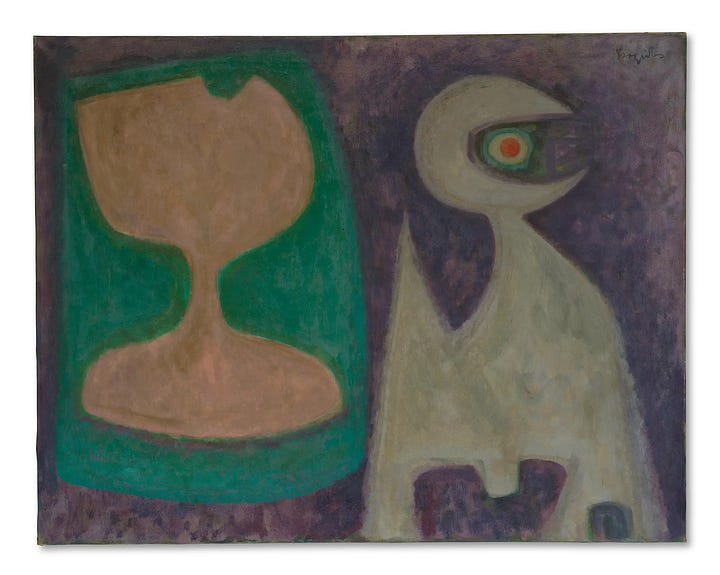

Also when Baziotes won the Carnegie (1948) there was a reproduction in the Times. I remember bringing it to class. It was source of bewilderment, delineated configurations that seemed to come out of Cubism. It was something new. Those were the tastes of a whole dimension that was to come, much more abstract and allover and I didn’t see much more of it until I came to New York.

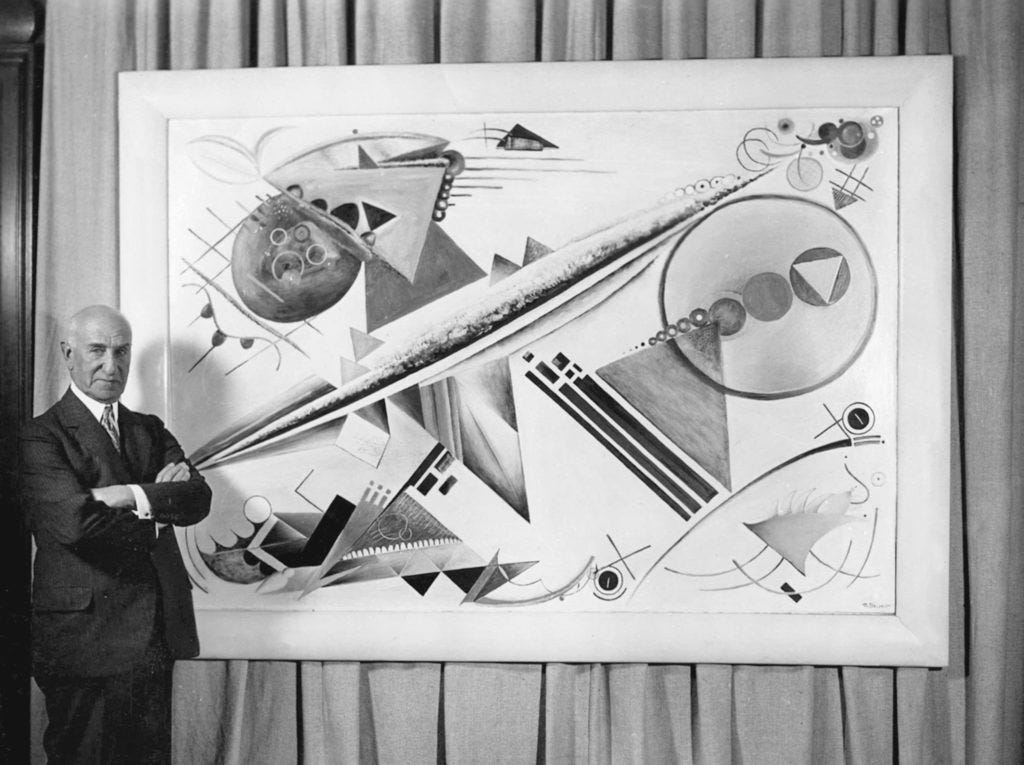

By my last year at school I knew I wanted to paint, was a painter. I continued in the Cubist vein but began to move on. I went to Columbia where I took a fascinating course with Meyer Schapiro, but realized I was going to Graduate School in Fine Arts mainly to make the painting legitimate for my family, so I dropped it to paint and look at pictures. I would go to the old Guggenheim to look at Kandinsky. I liked the early abstractions but the later ones I didn’t like at all.

Wallace Harrison (not the architect) ran a school in New York on 14th Street where I met James “Jim” and Charlotte Brooks.

I had studied with Harrison during 1948–1949, my non-residence term from Bennington. He had a school much like Hans Hofmann’s. He was an Australian and a passionate Francophile. His school taught the principles of Cubism much as did Hofmann’s. He had a big effect on me, coming when he did. He had us do typewriter-page sized drawings in pencil, in Cubist or Mondrian or Lipschitz idiom. We would work a drawing for weeks, erasing until we had what was—in his idiom—more important than a painting. We had learned a style thoroughly.

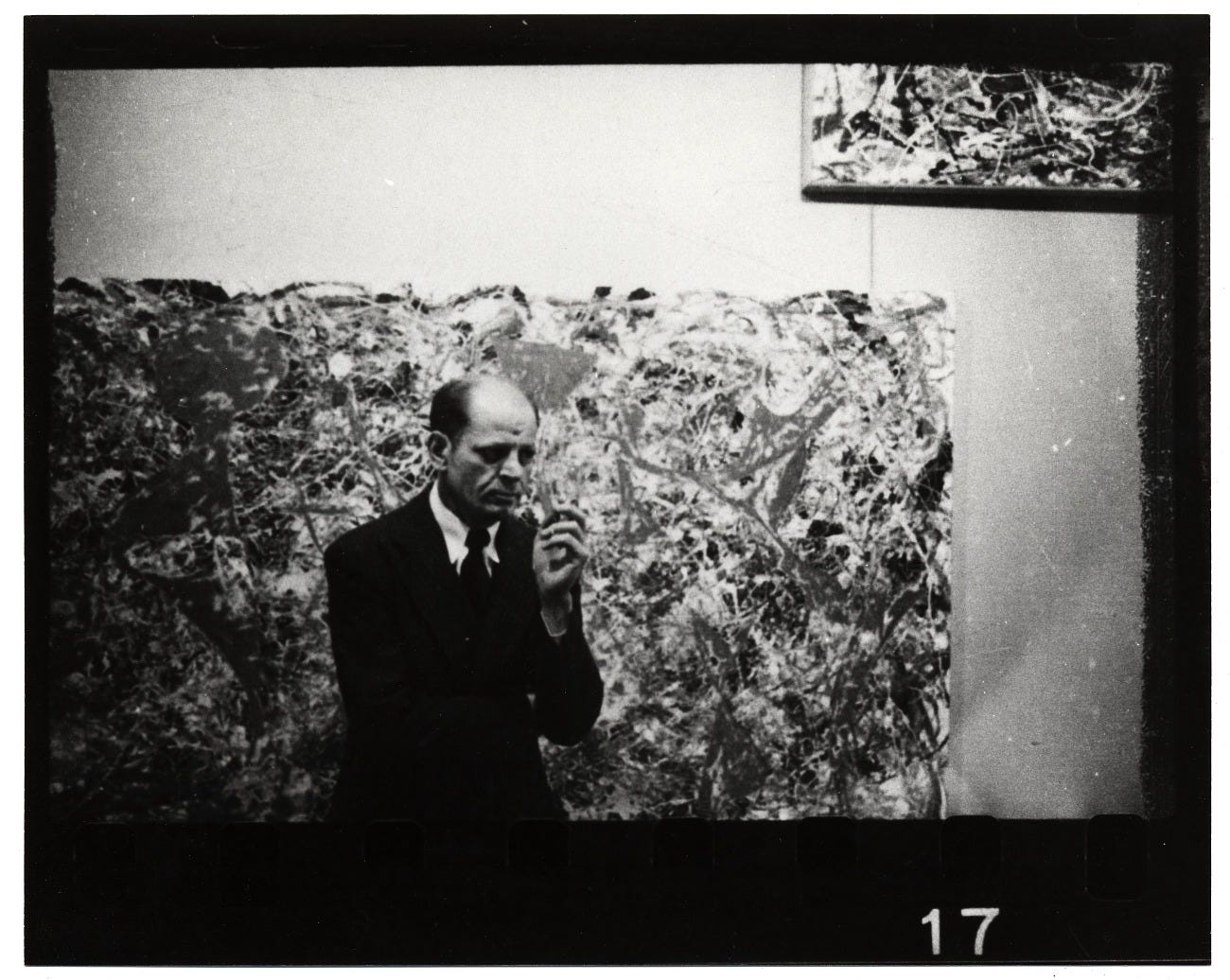

When did you first see Pollock?

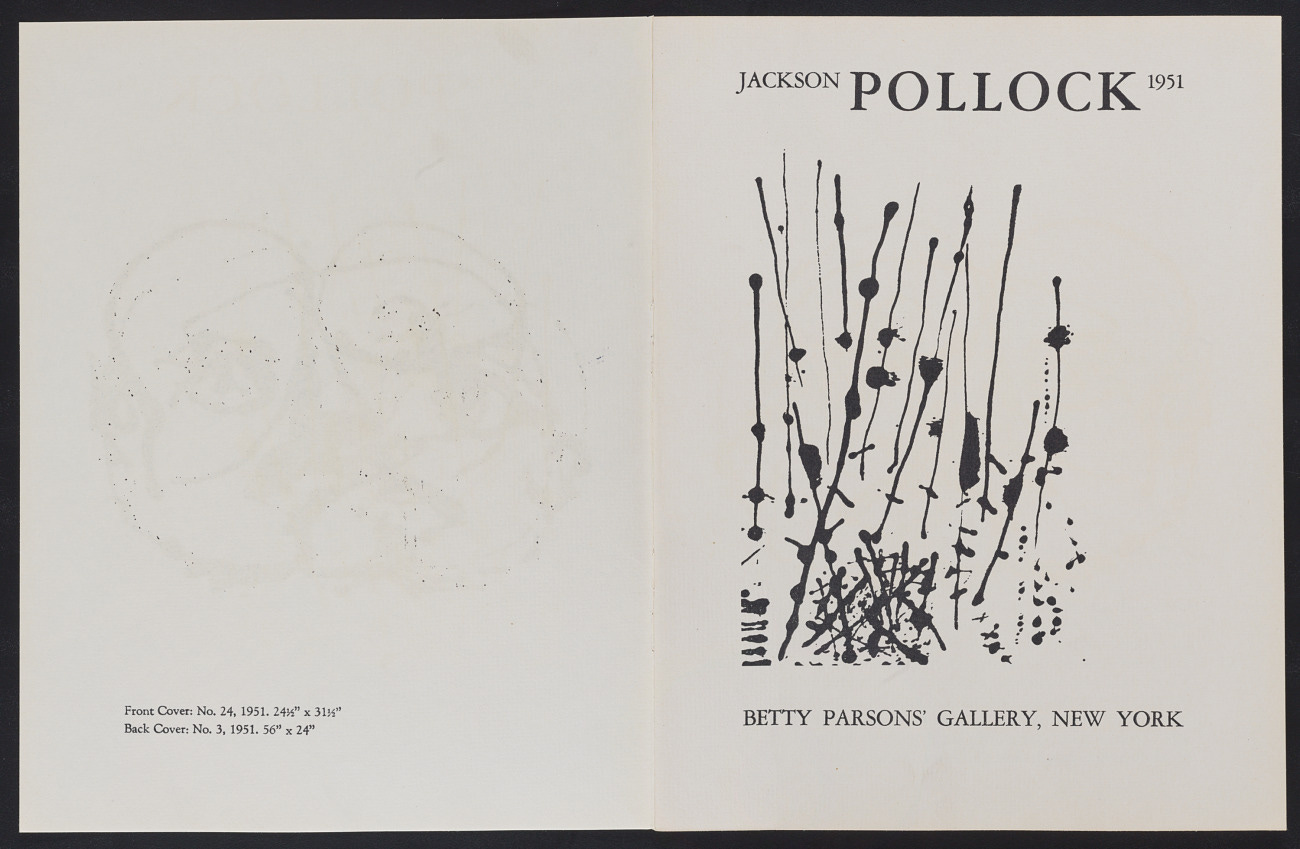

The first Pollock show I saw was in 1951 at Betty Parson’s gallery, early in the fall, probably September or October. It was staggering. I really felt surrounded. I went with Clement Greenberg who threw me into the room and seemed to say “swim.”

By then I had been exposed to enough of it so it hit me and had magic but didn’t puzzle me to the point of stopping my feelings.

Did it affect your work?

No, not immediately, within months. I went out to Springs and saw Pollock and his work, not only the shows. In 1951 I looked at [Willem] de Kooning as much as at Pollock. Earlier Kandinsky and Gorky had led me into what is now called “Abstract Expressionist” painting; but these came after all the Cubist training and exercise. It all combined to push me on. Like Cubism which it came out of, painting in the de Kooning, Gorky idiom was first revealing, then inhibiting to me.

I felt many more possibilities in Pollock’s work. That is, I looked at and was influenced by both Pollock and de Kooning and eventually felt that there were many more possibilities for me out of the Pollock vocabulary.

De Kooning made enclosed linear shapes and “applied” the brush. Pollock used shoulder and ropes and ignored the edges and corners. I felt I could stretch more in the Pollock framework. I found that in Pollock I also responded to a certain Surreal element—the understated image that was really present: animals, thoughts, jungles, expressions. You could become a de Kooning disciple or satellite or mirror, but you could depart from Pollock. Also the de Kooning way offered a life. He lived in New York, Pollock in Springs.

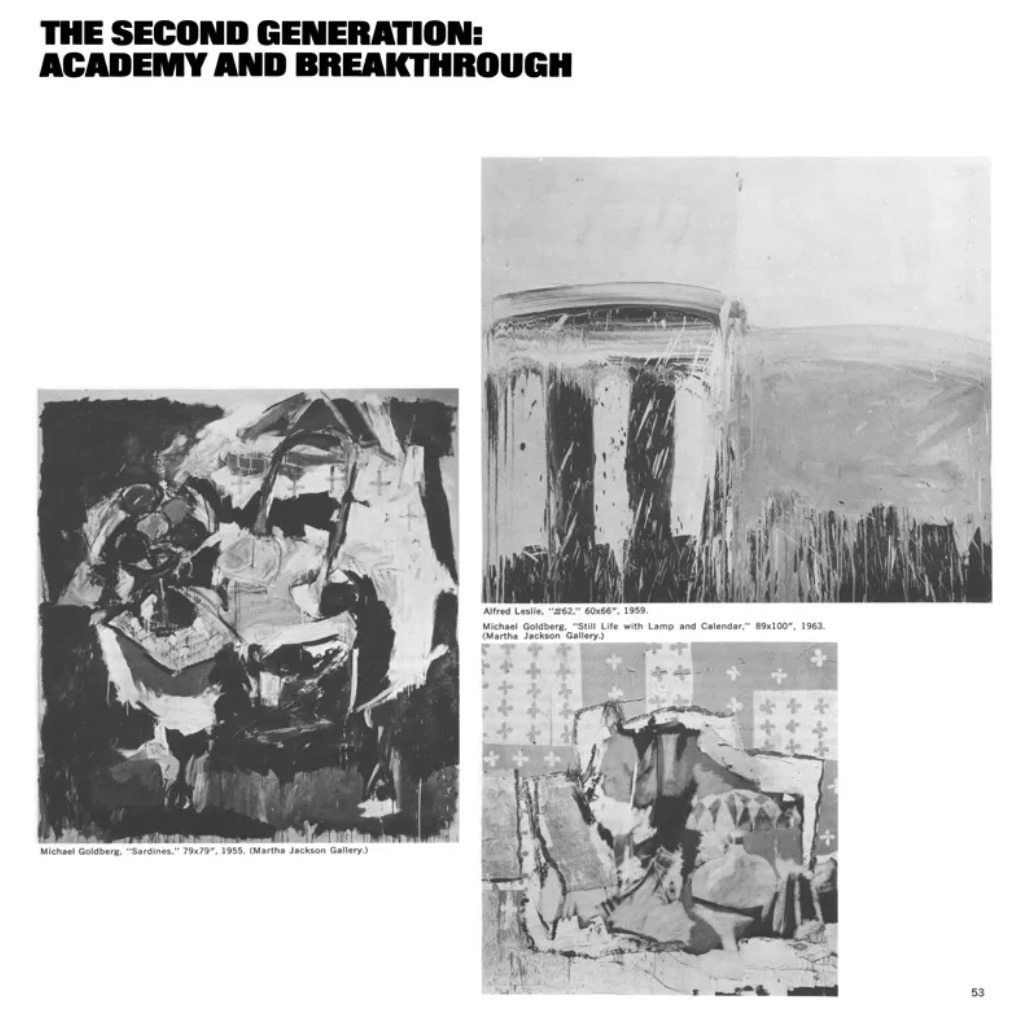

The younger painters were polarized one way or the other. At first it was all of us together, young and honoring our mentors. We were the second generation, they were the first. Then, we “broke up” according to sensibilities.

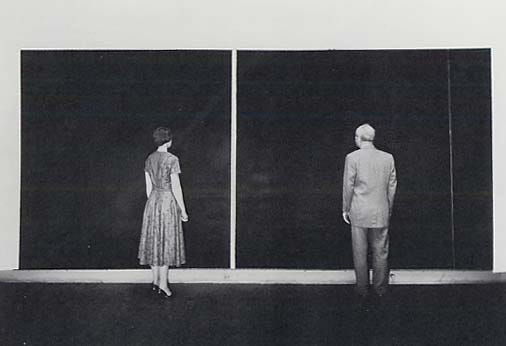

How about Barney Newman?

I saw Barney [Newman]’s show at Betty Parson’s in 1951. It was very eccentric. I felt its importance, respected it, but wasn’t up to it.

Is there anything in your work still of Cubism?

Yes, I still, when I judge my own pictures (either while I’m working or after I think it’s finished) determine if they work in a certain kind of space, through shape or color.

I think all totally abstract pictures—the best ones that really come off—Newman, Pollock, Noland—have tremendous space; perspective space despite the emphasis on flat surface. For example, in Noland a band of yellow in relation to a band of blue and one of orange can move in depth although they are married to the surface. This has become a familiar explanation, but few people really see and feel it that way.

The way an inch of space behind a banjo in a 1912 Picasso has depth. And the ones that go dead and static can’t be read that way; they don’t move. In my work, because of color and shape a lot is read in the landscape sense. I don’t think Newman is “landscape” or Noland, although when you think of vast open spaces one tends to think in landscapes, not emptiness.

Who did you talk to about pictures in the early fifties?

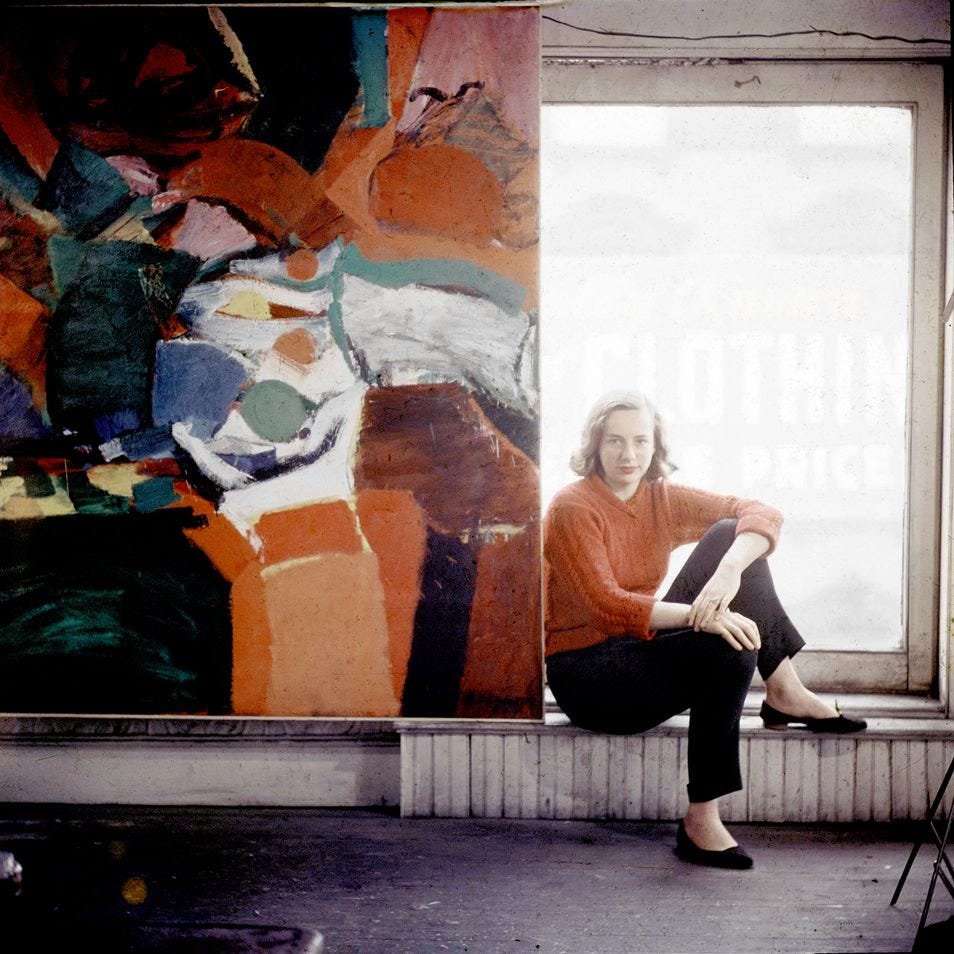

The people I talked pictures with or those who encouraged me to make discoveries included Clement Greenberg, Friedel Dzubas, Grace Hartigan, Sonja Rudikoff.

What was marvelous was that you didn’t feel everyone was “doing it.” The group and the audience were small. Now you feel in New York that people are making yards of painting behind every house facade and taking them across the street to miles of galleries. Then, individual paintings evoked specific responses. We all went to the Club Friday nights. I saw a lot of Grace, and Al Leslie and Harry Jackson.

Later our lives and allegiances and values all changed and were rearranged—they do, as you develop through crucial years. Often what is heralded as “newest” now is felt less profoundly than in preceding decades. I think the whole engagement doesn’t tickle the brain the way it used to—there are other dimensions. It’s increasingly evident that Abstract Painting is the main issue—continued, pursued, developed by the first and second generations and now by younger abstract artists. There’s still a lot to be revealed.

Has the art world changed since the early ’50s?

I think when you’re really painting, involved in a painting, what goes on in the art world doesn’t matter. When you’re making what you have to you’re totally involved in the act. Now, the moment you get out of the studio it can be a very sad scene. A lot of it, from my point of view might seem sad because I have such good memories of being a young painter in New York. For all I know, if I were twenty today, it would be as “exciting.”

When we were all showing at Tibor de Nagy in the early fifties, none of us expected to sell pictures. A few people knew your work. There was a handful of people you could talk to in your studio, a small orbit. Outside, there were Art News, Arts Digest, The Times, and the Parsons Gallery, Janis, Kootz, Egan. Johnny Myers at Tibor was the first to take the younger artists, in a railroad flat on 53rd Street, between Second and Third, before 10th Street or the Stable.

Sometimes I think the worst thing is the current “worldliness” of the whole scene. It is the most deceptive, corrupting, transient thing, full of kicks and fun but so little to do with what it’s all really about. There are too many people who surround themselves with different samples of power, and so many “working” props—if you live long enough on a Hollywood set the street almost becomes real. You can count a very few who don’t care about the world in that way. If enough people are behind something, it can be anything, it gets a big call. It has to do with our time, a desperate pact about the power of immediate in-ness. But I feel less and less concerned with this as an issue. So what? No threat.

Was there any postwar European painting you were interested in?

Miró. Matisse. But more Miró. As I’ve said I’ve been touched, in the work of Miró and Pollock, by a Surrealist—by Surrealist I mean “associative”—quality. It’s what comes through in association after your eye has experienced the surface as a great picture; it is incidental but can be enriching.

Gorky too has affected me this way, but in Gorky, though it fascinated me, it often got in my way. I was too much aware of, let’s say, what read as sex organs arranged in a room.

I liked the big 1961 Miró Blue II in the Guggenheim show several years ago very much. He often has that thing I respond to in Pollock. It’s the role that the image plays; in a sense it is totally irrelevant to the esthetics of a work of art, but in another sense it adds a profound dimension, as certain webs of Pollock’s became decipherable characters. It isn’t the image that makes it work for me, it is that they are great abstract pictures. I leave it out of my own pictures more and more as I become increasingly involved with colors and shapes. But it is still there.

How do you name your pictures?

I’m very poor at naming them. I don’t like numbers because I don’t remember them. The only number I’ve ever remembered is Pollock’s No. 14 which to me has a sort of “fox in the woods” in it. I usually name them for an image that seems to come out of the pictures, like Blue Territory, or I look and see Scattered Shapes, or Red Burden. I don’t like sentimental titles. A picture like Small’s Paradise had a Persian shape in it; also I’d been to that night club recently. One names a picture in order to refer to it.

In 1951 I did a picture called Ed Winston’s Tropical Gardens. It was a juke box bar on 8th Street, filled with celluloid palm trees and five-and-ten-cent store Hawaiian decor. The painting is 18 feet long. I had the memory of the place and did a sunny green and yellow landscape. It’s more difficult to title more abstract pictures.

Do you start your pictures with a plan or look in mind?

I will sometimes start a picture feeling “What will happen if I work with three blues and another color, and maybe more or less of the other color than the combined blues?” And very often midway through the picture I have to change the basis of the experience. Or I add and add to the canvas. And if it’s over-worked and beyond help I throw it away.

I used to try to work from a given, made shape. But I’m less involved now with the shape as such. I’m much more apt to be surprised that pink and green within these shapes are doing something. After ’51–’54 I had a long involvement with lines and black. Then that got played out.

What do you mean by gesture?

When I say gesture, my gesture, I mean what my mark is I think there is something now I am still working out in paint; it is a struggle for me to both discard and retain what is gestural and personal, “Signature”. I have been trying, and the process began without my knowing it, to stop relying on gesture, but it is a struggle. “Gesture” must appear out of necessity not habit. I don’t start with a color order but find the color as I go.

I’d rather risk an ugly surprise than rely on things I know I can do. The whole business of spotting; the small area of color in a big canvas; how edges meet; how accidents are controlled; all this fascinates me, though it is often where I am most facile and most seducible by my own talent.

The gesture today is surely more purely abstract than it was. There is a certain moment when one can look so pure that the result is emptiness—many readings of a work of art are eliminated and you are left with one note that may be real and pure but it’s only that, one shaft. For example, the best Mondrians, Newmans, Nolands, or Louises are deep and beautiful and get better and better. But I think that many of the camp followers are empty.

When you first saw a Cubist or Impressionist picture there was a whole way of instructing the eye or the subconscious. Dabs of color had to stand for real things; it was an abstraction of a guitar or of a hillside. The opposite is going on now. If you have bands of blue, green and pink, the mind doesn’t think sky, grass and flesh. These are colors and the question is what are they doing with themselves and with each other. Sentiment and nuance are being squeezed out so that if something is not altogether flatly painted then there might be a hint of edge, chiaroscuro, shadow and if one wants just that pure thing these associations get in the way.

How do you feel about being a woman painter?

Obviously, first I am involved in painting not the who and how. I wonder if my pictures are more “lyrical” (that loaded word!) because I’m a woman. Looking at my paintings as if they were painted by a woman is superficial, a side issue, like looking at Klines and saying they are bohemian. The making of serious painters.

One must be oneself, whatever.

How long have you used the acrylic paints?

I’ve been using acrylic paint for three years and I like it more and more but it’s been difficult to learn how to use it; the way it dries, how thin or creamy, in what conditions you can work over it—not a real problem for me as I rarely work over an area.

When scratched it can’t be easily repaired; the quality of the paint can be scratchy, tough, modern, once removed you’re not as involved in metier, wrist or medium as is often the case with oil. At its best, it fights painterliness for me, it tends to retain its color. Oil and turpentine can fade on unsized, unprimed cotton duck; not that it always hurts a picture, but I’d rather a picture didn’t fade.

Why did you try the acrylics?

I thought if there’s a paint around that is durable, dries so quickly, let’s try it. And I often force myself to try something new just to “move on” and see the results. I tried, didn’t like it, went back to oil, then tried it again. I might just get back into oils again at some point—I like to feel it’s all open and possible. I don’t think that the new acrylics necessarily go with new abstraction any more than plywood has to go with modern houses.

When a picture needs blank canvas to breathe a certain way I leave it. If you look at my pictures over the years, the first breakthrough in leaving blank canvas left a lot of it “blank”; progressively it was covered up, until now my best pictures are sometimes totally covered. When I order stretchers for pictures with unsized canvas, nine out of ten times I cut off the blank areas because the picture doesn’t need them. This is an aspect of giving up one’s “mark.” The unsized area doesn’t have to do the work. That doesn’t mean I couldn’t—don’t—do pictures that need unsized areas. Often what I seem to fight is the idea that I’m on to something and going to drive it into the ground. I tend to side-develop, not to hang on, but in seeming to side-develop that’s the way I really show my mark and continuity.

Related Notes:

Okay, a little more extra fun!

Reading list: Ninth Street Women, Fierce Poise, The Slip, Lee Krasner: A Biography, and Leap Before You Look.

The New Yorker, on imagining the Abstract Expressionism scene while visiting Helen Frankenthaler and Morris Louis exhibitions—it’s Painting After Pollock.

A Color (Field) Story: How One Woman Changed the Course of Abstract Expressionism

Really need to find time to read the transcript of the Tibor de Nagy oral history from the Smithsonian Archives of American Art.

**

Kelsey Rose

Helen’s work is sublime! This was such a fascinating read ✨ thank you, as always!

Wow! Thank you for this beautiful post.