BOOK CLUB vol. 5: The singular book on Hans Hofmann's School of Fine Arts supply list

Reading "Expressionism in Art" thanks to the precise recommendation of a world-famous Abstract Expressionist.

*This email may be truncated in your inbox. To make sure you are reading the entire post, please move yourself along to a web browser!

Normally, my BOOK CLUB series focuses on the interior spaces or advertising campaigns of people and/or brands. I adore being able to snoop photographs (or even better: take tours of historic homes) in order to see what people I admire were/are reading. Or—maybe just collecting—because sometimes we don’t get around to the reading part!

I want to do this installment a little differently.

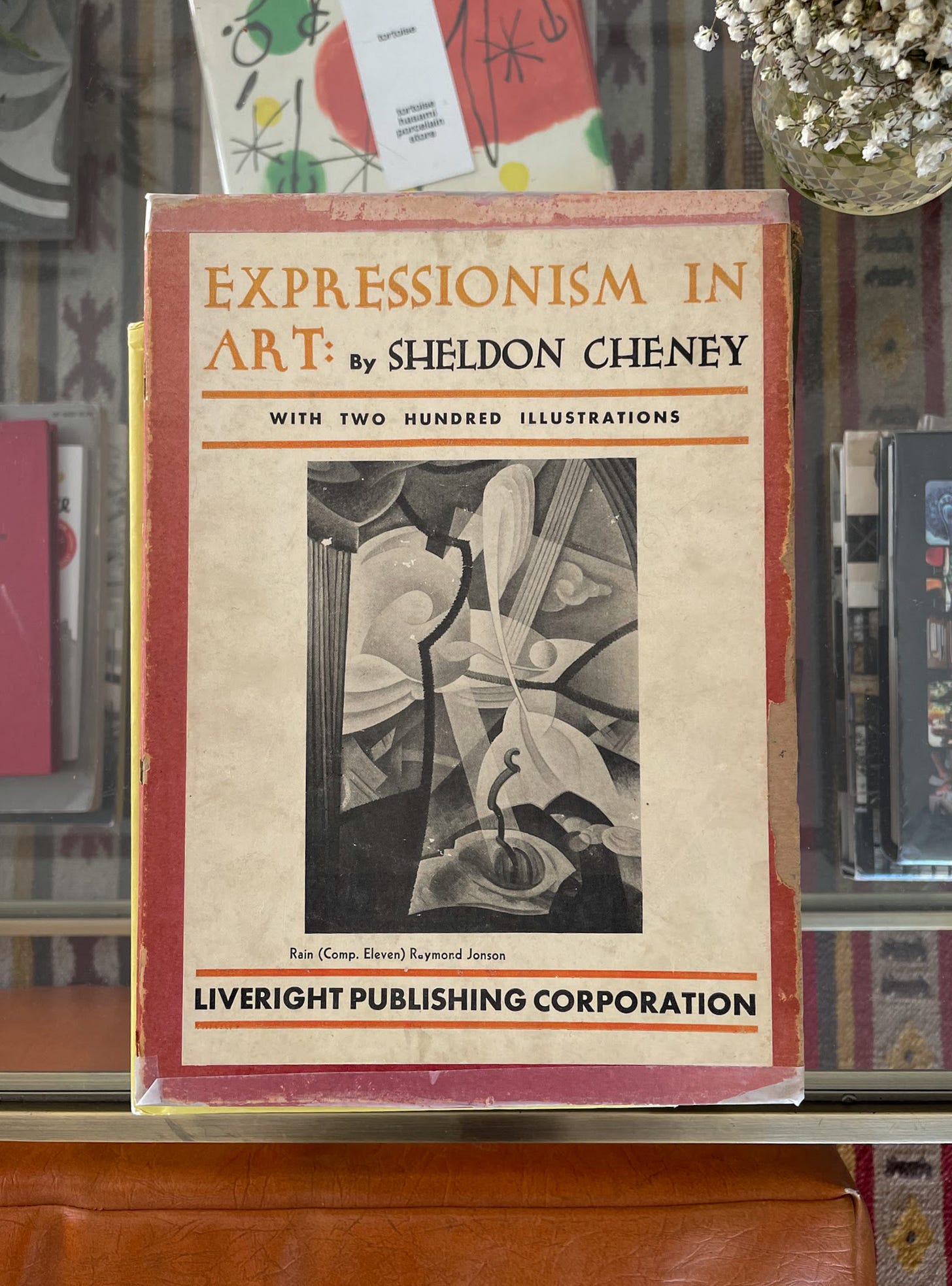

Modern painter and educator Hans Hofmann prescribed one book to his students on an introductory syllabus for his art school, the Hans Hofmann School of Fine Arts in Provincetown, Massachusetts. The first line on the syllabus read: “It is recommended to students planning to join the Hans Hofmann School to read Sheldon Cheney’s (1934) book - Expressionism in Art.” The remainder of the page described the extensive and “necessary materials” for drawing and painting— all of which, as noted, could be purchased upon arrival in Provincetown. An outdoor easel, turpentine, charcoal paper, Rubens no. 7 flat brush with “some short, some long bristles,” oil paints in specific colors (cadmium lemon, cerulean blue, alizarine crimson, burnt umber, etc.), and…Expressionism in Art.

I got my hands on a vintage 1st edition copy as soon as humanly possible and it has been sitting on my desk in all of its tattered glory for nearly a year. I’ve been itching to read it, obviously, but I felt (and still feel) intimidated by its importance! Before reading it, I wanted to peer into the layered history of Hofmann, his school for the arts, and to think a little deeper about why he might have chosen this exact book. What messages did it have for art students at the time? Why was it the only book Hofmann listed?

Like my usual BOOK CLUB writings, I’ll include some of my personal recommendations at the end. Think of these as what I’d urge my own imaginary art students to read. Or, if his Provincetown school still existed and I had the luck to be a student, this would be a short list of what I would gravitate toward and share with my most-trusted classmates. Pretending I was there in Provincetown is my idea of a thrilling time!

Previous BOOK CLUB issues:

Vol. 1 - French clothing brand Sessún

Vol. 2 - Dakota Johnson’s Architectural Digest home tour

Vol. 3 - Finn Juhl's Copenhagen modern house

Vol 4 - Catalan architect Ricardo Bofill and his lofty bookshelves in Barcelona

Who was Hans Hofmann, and what’s this about his school for art?

“Hans Hofmann (1880–1966) is one of the most important figures of postwar American art. Celebrated for his exuberant, color-filled canvases, and renowned as an influential teacher for generations of artists—first in his native Germany, then in New York and Provincetown—Hofmann played a pivotal role in the development of Abstract Expressionism.

Between 1900 and 1930, Hofmann’s early studies, decades of painting, and schools of art took him to Munich, to Paris, then back to Munich. By 1933, and for the next four decades, he lived in New York and in Provincetown. Hofmann’s evolution from modern art teacher to pivotal modern artist brought him into contact with many of the foremost artists, critics, and dealers of the twentieth century: Henri Matisse, Pablo Picasso, Georges Braque, Wassily Kandinsky, Sonia and Robert Delaunay, Betty Parsons, Peggy Guggenheim, Lee Krasner, Jackson Pollock, and many others. His successful career was shepherded by the postwar modern art dealer Sam Kootz, secured by the art historian and critic Clement Greenberg, and anchored by the professional and personal support of his first wife, Maria ‘Miz’ Wolfegg (1885–1963).

Already 64 by the time of his first solo exhibition at Art of This Century in New York in 1944, Hofmann balanced the demands of teaching and painting until he closed his school in 1956. Doing so enabled him to renew focus on his own painting during the heyday of Abstract Expressionism. For the next twenty years, Hofmann’s voluminous output—powerfully influenced by Matisse’s use of color and Cubism’s displacement of form—developed into an artistic approach and theory he called ‘push and pull,’ which he described as interdependent relationships between form, color, and space. From his early landscapes of the 1930s, to his ‘slab’ paintings of the late 1950s, and his abstract works at the end of his career upon his death in 1966, Hofmann continued to create boldly experimental color combinations and formal contrasts that transcended genre and style.”

Notable students of his school of fine arts included Lee Krasner, Ray Kaiser (for 6 years, before she became Ray Eames), Franz Kline, and Mark Rothko. From Hofmann, they learned to be exacting in their mastery of color, form, and composition. While thinking of how his courses must have compared to (my beloved) Josef Albers and the Black Mountain College education, I stumbled upon this great description by The Art Story:

“By the 1940s, Hans Hofmann and his school had emerged as the philosophical opponent of Josef Albers, the Bauhaus-trained artist who was heading the arts curriculum at Black Mountain College in North Carolina. While Black Mountain stressed the importance of learning and mastering a variety of techniques (easel painting, sculpture, choreography, architecture, etc.), Hofmann's curriculum was far more rigid. His students learned to become proficient in their studio work and focus on a single artistic medium, which for most of Hofmann's students was easel painting.

While Black Mountain offered a range of different instructors and artistic experiences, Hofmann preferred a narrower approach. As the school's sole teacher, he worked with each of his students individually to ensure they received an education in the fundamentals and history of their particular medium.

As a temporary artists' colony, Black Mountain offered its students an exciting world of social networking in a rural environment—a sort of displaced slice of New York City life in the North Carolina woods. Hofmann designed his school as a complete escape from the urban bustle, believing students should completely immerse themselves in the studio. Larry Rivers once recalled that the Hofmann School was removed from ‘any notion of Art school relaxed bohemia with its sex and good times abounding.’ The Hofmann School was a formal and stringent environment for artists; once students had mastered their craft, they were free to go out into the world and do as they pleased.”

About the ONE book he advised his students to read:

Sheldon Cheney (1886-1980) was an art critic, historian, theatre magazine editor, and book author—including the special one we’re talking about here! His personal papers are archived at the Smithsonian’s Archives of American Art and include mention of Alfred Stieglitz, Aline Barnsdall (for the LA dwellers here, she’s the one that commissioned Barnsdall Art Park/the Hollyhock House), Andrew Wyeth, and an editor of Playboy. A varied list! I wonder: after learning a little backstory about Cheney—did his theatrical appreciation help him leap forward into understanding the frenzied world of abstract expressionist modern painting?

After researching a little more about the level of precision and meticulousness that Hofmann expected from his pupils, I can better understand his reasoning for choosing this one and only book, Expressionism in Art. It was new at the peak time of Hofmann’s Provincetown courses, so, it was up-to-date. The book is comprehensive, covering the history of an extensive list of important modern people, terms, and places up until its publication. And, the book was from a trustworthy source. Cheney was esteemed in writing titles about art, just as Hofmann was about teaching painting.

After asking “What is Expressionism?” in a chapter’s title, Cheney broke out his answer into digestible themes. Expressionism, is, and can be:

getting to the soul of the object

the expressiveness of materials

seeing, understanding, and creating

a backward-forward movement

respecting the surface plane

the path of main movement

opening the picture

movement start, and movement control

“Why Expressionism? I believe Expressionism to be the name history will assign to the development in art that began with Cézanne in painting, with Sullivan in architecture, with Duncan in dancing, with Craig and Appia in the theatre. It seems to me the only term exact enough to describe alike the works of Cézanne and Picasso and Orozco and Wigman and Wright and Lehmbruck; even while broad enough to embrace the varied contributions of the so-called Post-Impressionists, Fauves, Cubists, Functionalists, Purists, etc.

There are enough books serving as introductions to Modernism, recounting its early history and paving the way to the first glimmers of understanding. But there is, in English, no book pretending to analyze the characteristic elements in Expressionist art. . .I was trying to remove the blinders placed by academic teaching over the eyes of the average citizen, was hoping to pry open, a little, the too tightly enclosed mind of the student and observer.

My first aim is to aid the student in opening the way to understanding and enjoyment. I hope, in addition, that practicing artists will find the book clarifying; though I want no one to seek herein a formula for creative accomplishment. True Expressionism goes deeper than that.

The book is at once my most independent and personal expression upon art, and a confession that I have no original theory of Modernism. Even while relying upon my own reactions to and study of living art works, I can claim no originality for the explanations and analyses set forth…I have merely collated more recorded opinions and expositions that any earlier writer, and I am attempting a digest in readable form, along the line of my own ‘seeing.’

But it is for the book itself to explain what Expressionism is: how the artists now arrive at a more intense expressiveness (instead of of simulating aspects of nature, or echoing Greek architectural idioms), and what it is that they express.

In all reverence I may say, God help me!”

S.C.

Berkeley, CA,

October 1934

Perhaps with a bias, Hofmann may have prescribed this text to his students because his own name and theories were scattered generously throughout. “By far my largest debt, however, is to Professor Hans Hofmann,” declared Cheney in the preface. “Hofmann’s exposition of the formal part of the Expressionist synthesis seemed to me clarifying beyond any previous statements.”

Cheney’s love letter to Hofmann continues in the middle chapters:

“No one else has written quite so clearly as Hofmann, I think, regarding the matter of basic volume-composition. He points out that volume and space as materials may be conveniently considered as filled space and empty space: as positive space and negative space.

In The Aims of Art [Hofmann] writes:

‘Form must be balanced by means of space. We differentiate the animated form and the space pervaded by energy. Form exists because of space, and space exists because of form. A work of art which expresses only the objective form always has an over-emphasized naturalistic effect. The spatial counterbalance being omitted, the painting misses the inner rhythm. . .

From the depth-sensation, movement develops. There are movements into space and movements forward, out of space, both in form and in color. The product of movement and counter-movement is tension. When tension—working strength—is expressed, it endows the work of art with the living effect of coordinated, though opposing, forces. Tension and movement, or movement and counter-movement, lawfully ordered within unity, paralleling the artist’s life-experience and his artistic and human discipline, endow the work with the power to stir the observer rhythmically to a response to living, spiritual totality.

The picture swings, oscillates, vibrates with form-rhythms integrated to the purpose of spatial (and volumnar) unity and it resonates with color rhythms balanced, focussed, and so ordered as to produce the richest intensity of light contrast. It is not the contrast of two or three, but the contrasted balance of many contributing factors, which produces the paradox of life within unity.’”

Five books I would recommend to people who wish they could have been Hofmann’s students (or Josef Albers’s):

The Story of Modern Art by Sheldon Cheney

Ninth Street Women by Mary Gabriel

Interaction of Color by Josef Albers

The Slip: The New York City Street That Changed American Art Forever by Prudence Peiffer

Leap Before You Look: Black Mountain College 1933-1957 by Helen Molesworth

**

Happy, expressionistic reading!

Kelsey Rose

Even if you don’t have a Substack, please feel free to like and/or leave comments. I love hearing from all of you!

PS - A number of these books above are linked to Bookshop.org, which is my absolute favorite place to buy books online. Bookshop.org works to connect readers with independent booksellers and stores all over the world. Since 2020, they’ve raised more than $28 million for independent bookstores—which is 28 million times better than supporting Amazon. You can see/shop my Bookshop here! I do get a teeny, tiny commission off of every book sale purchased directly from these links or from my Bookshop store front. I’ll only link books if I honestly believe in their goodness.