THE BARN of modern architect A. Quincy Jones

No goats or pigs—only an incredible book collection and Eames furniture galore!

❥ This email may be truncated in your inbox. To make sure you are reading the entire post, please move yourself along to a web browser!

More from me + Absolument can be found in these places:

Website | Instagram | Shop Absolument | Book Recs - Merci, thank you tons and tons for reading!

In 1966, photographer Julius Shulman arrived at a newly renovated New England-style residence in western Los Angeles, California. He was prepped for what became known to himself—and us archivists and researchers—as Job 3998, the A. Quincy Jones house and work studio. Most affectionately, this not-very-LA place was known as “The Barn.” Likely the only barn where there are no goats or pigs or horses present.

In the 1950s, the building was used as a photography studio. Modernist architect A. Quincy Jones purchased and remodeled it in 1965, making sure it was transformed into a unique place for both life and work.

At first, it was a traditionally red barn. His renovation began with painting it entirely white.

“Whatever it might be called, The Barn exudes a welcomed gentility,” wrote Sam Hall Kaplan, in his 1988 LA Times article, Quincy Jones, the Architect and His Legacy: Home Edition. Elaine Sewell Jones, the architect’s wife and one-half of The Barn’s dwellers, shared a short and sweet insight with Kaplan about the oeuvre of A. Quincy:

“His designs grew out of the problems, and within the constraints of materials, space, the site, and the budget. And always on his mind was the need of the user, the people who would use the building, whether a place to live, or work, play or worship. That’s what his architecture was all about.”

Elaine’s specific words about her husband’s projects admitted that: “designs grew out of problems and within the constraints of materials.” This sentiment immediately linked me to Charles and Ray Eames, whose design jargon was almost identical. Constraints, materials, and solving problems—all are hammered-down Eames philosophies.

Before she became a Jones, Elaine was a well-connected design and arts publicist. Among her roster of prolific clients were the Eameses themselves.

Kenneth Caldwall wrote about his time spent with Elaine while writing about her and A. Quincy for LA Architect magazine. “[Elaine] told me once about taking a trip to Carmel with Ray [Eames]. During the day, they went their separate ways and connected again in the late afternoon. They had both purchased a piece of ribbon—the same exact ribbon. She saw what her clients saw.”

The Barn is notably brimming with Eames furniture. An estimated 90% of the things you’d place your hands, your food, your books, or your buttocks on while at The Barn were designed by Charles and Ray Eames. Actually, the Eameses’ self-built home—the 75-year-old modernist residence and studio that very narrowly survived LA’s recent Palisades fire—is also filled with a majority of their own furniture designs. Elaine saw what her clients saw…and designed. The house’s living room is lined with Eames Aluminum Group seating, close-to-the-Earth LTRs (low tables). The library boasts an Eames ETR—the surfboard-shaped coffee table—another LTR, a LAR (the low armchair with “Cat’s Cradle” base), and a pair of DCMs. Truly an Eames acronym paradise.

Julius Shulman also photographed the Eames House twice (in 1950 and 1958) before The Barn existed, but perhaps I’m getting distracted here!

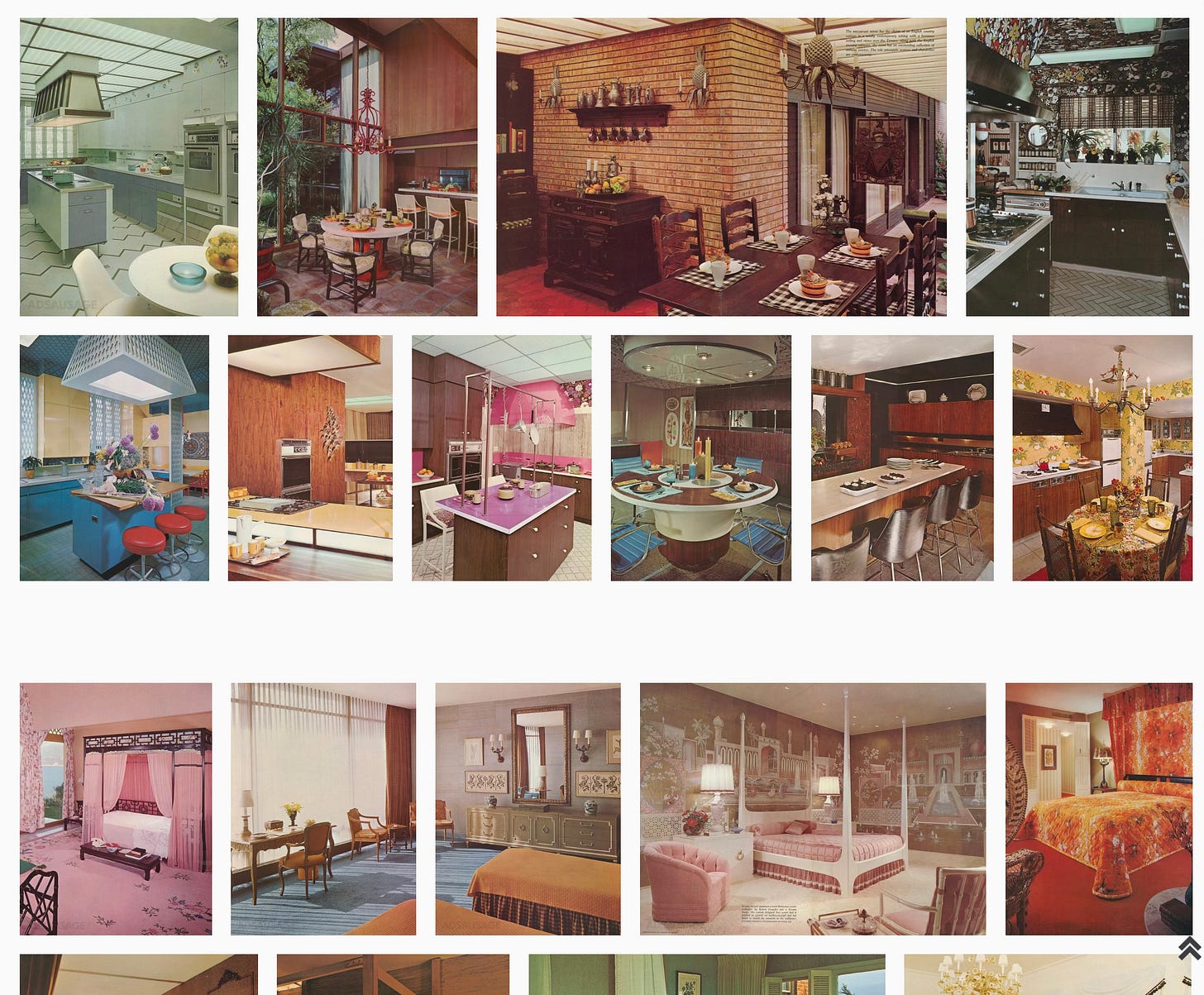

What was different about this house from the standard LA home of the time? Many elements. Its pitched ceilings, open floor plan, warehouse-like (OR: barn-like!) form, use of natural materials that were free of ornamentation (except a layer of white paint, in some cases), “modern” furniture, a sense of outdoors brought in by way of large plants, and expanses of glass to maximize sunlight.

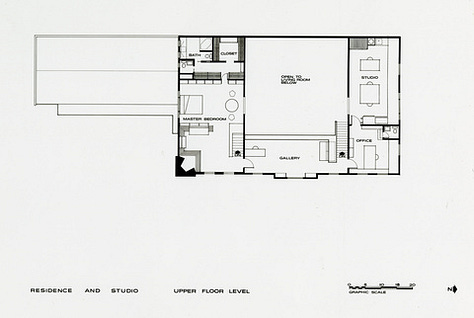

The biggest difference from other homes, though, was the mix of residential and work-related rooms. One-third of the property—the left-most side of the Barn—was dedicated to an architectural drafting studio and shop, which opened to an expansive outdoor patio. Even more, life and work weren’t too separated in the more “residential” two-thirds of the Barn. On that side of the property was an office and a library. The upstairs level was partially mezzanined—you could stand in either a gallery space or an additional studio to overlook the double-height living area. An extra office was tucked into a corner room.

In Dwell magazine, the leader of its “light-touch restoration” in 2008, Frederick Fisher, said of The Barn:

“When you’re in that building, you really feel you’re in the environment of two very sensitive, design-oriented people. . .It can be a workspace, a living space, an entertaining space, all in a very accommodating way. It’s in the tradition of the loft space, where artists have always been good at ferreting out live-work spaces that are under-appreciated or under-utilized. It’s neutral, mutable space that can be used in many different ways by a creative mind. It’s a good model for that and still quite relevant.”

For people like Elaine and A. Quincy Jones, who worked in creative, yet business-centric industries, there was hardly separation between church and state. Or more appropriately: life and design work.

These days, The Barn is even more oddly out of place than it was in the mid-60s. It was a change that was described even in that 1988 article in the LA Times. On three sides of the property are oppressively close, multi-story residences and office spaces. One recent build stacks personality-less one-bedroom apartments that cost $6k+ per month. On the fourth side, there is a bit of breathing room thanks to a slower street. But after a dinky median are the six lanes of traffic known as Santa Monica Boulevard: a promise of asphalted chaos! As on every corner of every city, especially after 60 years, things change.

Thankfully, The Barn’s interior continues to serve as its own oasis. It was purchased by the Annenberg Foundation, and now, Metabolic Studio uses it for artist residencies and archival projects. In 2023, it was added to the National Register of Historic Places (click here for more photos of every corner of the interior).

Related Notes:

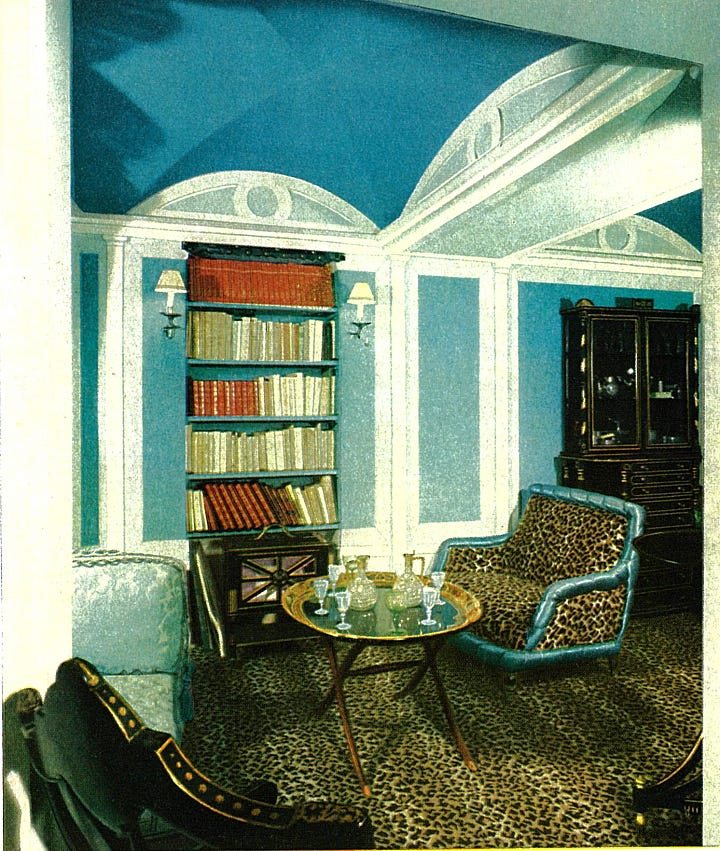

While searching for examples of “average” homes of the mid-1960s, I found a 1966 House & Garden interview of interior designer Madeleine Castaing. Definitely not average! One of her interiors reminded me of

’s recent writing, How to Turn Your Closet Into a Bode-ified Dressing Room. Mostly: the presence of a leopard print chair and red details within a blue-hued room.

I liked the way Castaing’s client relationships were described in the House & Garden interview:

Her special gift is undoubtedly that of being able to create homes for her clients which are uniquely their own. “But first they must let me have my way. If a client wants a boudoir a la Marie Antoinette, I simply say, ‘But, my dear, you are not Marie Antoinette.’”

But if they're not Marie Antoinette, who are they? Seeking out their identities takes time. She wants to know what books they read, whether they like or hate poetry, some thing of their tastes in painting, music, and so on. Such factors are more important to her than their preferences in colour or fabric. Those can come later. An astonishing footnote to all this is that her clients are apt to become her lasting friends.

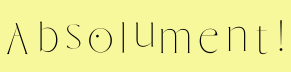

ADSAUSAGE’s Vintage Interiors 1966-1970 is a visual delight of color, texture, and pattern—especially in the carpeting department. Beige played a different role in the interiors of this time!

In January 1966, the first year the Joneses lived in The Barn, ARTFORUM wrote about “architecture now.” A fascinating read if you have the time to explore the nuances in modern architecture tendencies of that year.

If you want to be charmed by Julius Shulman, this documentary—which was released a few months after he passed away in 2009—remains one of my favorites in the telling of the modern movement of design.

**

Kelsey Rose