My life has winded me through many distinct chapters, all defined by geography. In 2016, I was two years into my Los Angeles segment, the one that I believe has defined my identity the most. At the time, I was working at the Eames House— organizing the photo archive, doing conservation projects with the Getty, and giving tours to eager Charles and Ray fans. I was answering what felt like one million questions per week about my favorite design and architecture subjects from people from all over the globe. In my free time, I read significant amounts about architecture, stalked houses from the sidewalk in my cherry red Volkswagen Cabriolet convertible, and tried to collect interior tours of as many historic homes as possible. I was greedy for this stuff—wanting to know more, more, more about this era and its off-the-shelf style of construction.

Occasionally I found myself housesitting a Neutra home next-door to the Eames House. Once, I was posing like the woman in a well-known Julius Shulman photograph inside a Case Study House. One of my favorite memories was helping a colleague cover up the sofas at his other place of work, the Stahl House, after a sunset tour. Often, I was hushedly recalling addresses of great homes to people who wanted to see the true treasures of LA architecture. I built my life upon the things other people had built in 1930, -40, -50, -60, and so on. I miss this chapter of my life very much.

At the time, my English coworker had introduced me to her expat group of friends who were living in LA, and I had met another group of Brits who were in a PhD research program at the Huntington Library. All of this British influence introduced me to UK-born architecture historian Reyner Banham. I began chanting his name whenever anyone needed an LA architecture-related recommendation.

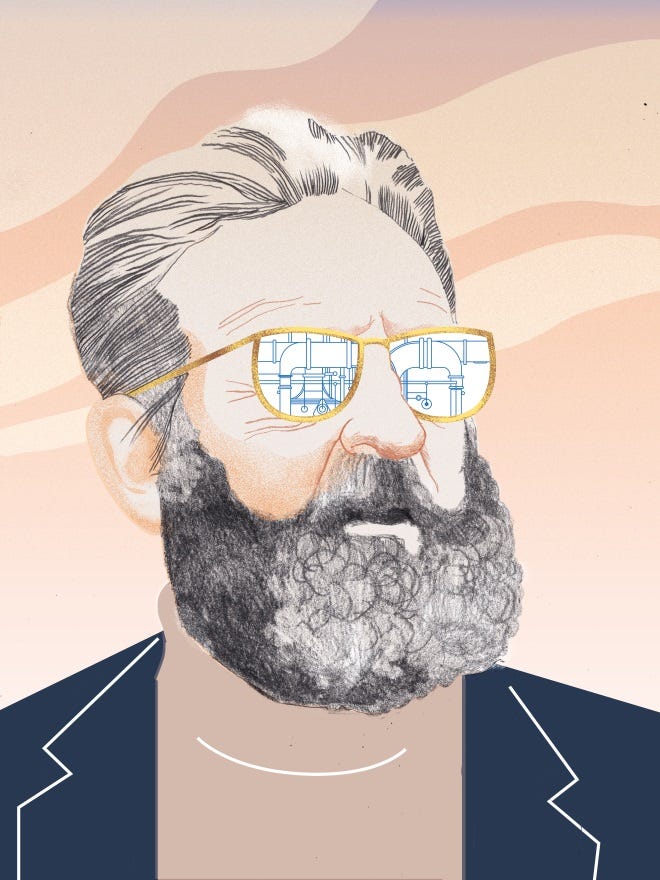

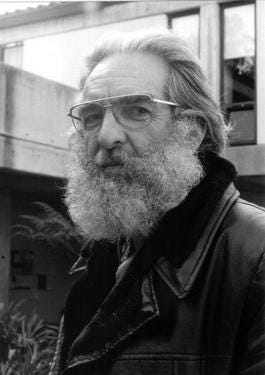

Who is Reyner Banham?

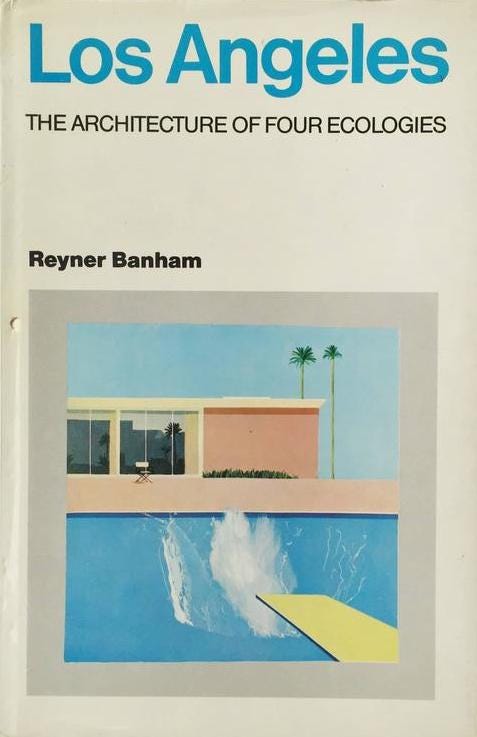

Besides being an all-around-cool-as-heck-kind-of-a-guy, Reyner Banham was a professor of architecture history at University College London, SUNY Buffalo, and UC Santa Cruz; a critic for ArtReview, Architectural Review, and dozens of publications; and author of multiple architecture titles that are definite staples in any architecture-obsessed person’s book collection. My favorite of his publications is Los Angeles: The Architecture of Four Ecologies, which “examined the ways Angelenos relate to the beach, the freeways, the flatlands, and the foothills.” LA may not experience four seasons, but these four terrains remain essential to the fabric of the city.

The New York Times declared Reyner as “among the first architectural historians to give the same degree of attention to the architecture of the everyday landscape that scholars give to monuments and cathedrals. He was particularly entranced with the American cityscape.” A clear line between all of his projects is his ability to mesh unapproachable theory and scholarship with his very personal feelings (which were tinged with British wit).

And why does he love Los Angeles?

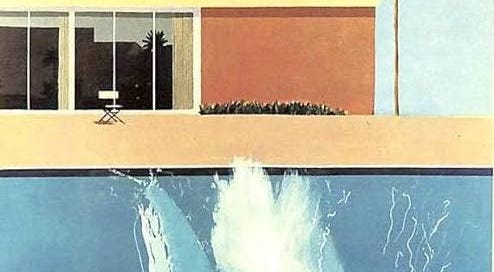

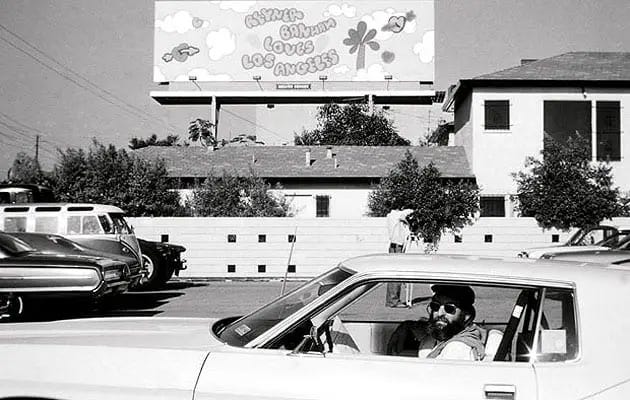

The film REYNER BANHAM LOVES LOS ANGELES (1972) begins with Mr. Banham crossing a street while narrating in his charming British voice: “You might wonder what I’m doing in Los Angeles, which makes nonsense of history and breaks all the rules. Well, I love the place with a passion that goes beyond sense or reason.” He loads himself into his slick 1970s car (nicknamed the Baede-Kar). It has a built-in Siri-esque navigational voice who helps him traverse around the streets of LA. “Devising a guide is a good way to explain a city,” claims Banham, “and Los Angeles needs some explaining because it’s normally regarded as an unspeakable sprawling mess.” On the tour, you’ll sense Banham’s enthusiasm for the many stretches of concrete, the urbanist sprawl, and some of Southern California’s greatest hits (including the beloved Eames House).

Alongside the obvious charms of LA, Banham made sure to highlight the social and environmental elements that have negatively pressed and pushed the city and its inhabitants. You’ll learn about the conquest of Mexican land and the tourism of Olvera Street; Watts and its race riots; goofy Hollywood bus tours; the original streetcar rail lines; the importance of pedestrian movement in a car-centric city; Spanish Colonial homes as a “frame of mind, a special kind of LA mass-produced fantasy—domestic dreams that money can buy”; modern-era private residences, wellness movements of Venice; Marina del Rey as “a plastic ghetto with plastic people and plastic boats”; the purposeful destruction of Santa Monica Pier; and more. That’s quite the list of topics! But it’s the exact feeling that LA gives you: a sense of varied abundance and a bit of the absurd. During a scene in which Banham is lecturing to university students, he shares a surprising opinion: Los Angeles is a city that works. Fifty-one years later, would you agree?

You can watch the 50-something-minute documentary below and find yourself entranced during this slightly psychedelic trip around the 10, 101, and 405 freeways. Just a little warning: the footage isn’t in the best quality, but it is absolutely worth the watch! Especially the semi-love letter to LA’s pollution-filled sunsets at the end.

Other Notes:

As a result of my constant inquiries for a list of modern houses people should stalk, I put together a driving tour winding from Pasadena to the Pacific Palisades. If you have a car and a few hours of time, you can drive the long stretch of Los Angeles and see some of my most cherished homes from the comfort of your driver’s seat. It isn’t trespassing if you simply admire from the street! Here’s The Not-Trespassing Tour of Modern Homes in Los Angeles.

I remember watching a video of Charles Eames driving through Venice (in a very Reyner-like manner) in the 70s, dictating to a reporter about his architectural views of LA. He intelligently claimed that a lack of constraints is the reason why Los Angeles looks the way it does.

Esther McCoy’s Los Angeles reader is filled with writings about designers, projects, and places in Los Angeles beginning with McCoy’s time as a drafts(wo)man for RM Schindler in the 1940s. Esther, in my eyes, is LA’s mother of architectural writings.

The MAK Center assembles a tour every year (usually in October) of private modern-era homes all around LA. My favorite was 2016’s tour, which gave ticket holders access to 9 homes around Silver Lake, Echo Park, and Mount Washington. These homes were the big guns—designed by architects like Gregory Ain, Raphael Soriano, RM Schindler—and most times never shown to the public. I was a tour guide that year, so I got free roam of the houses after my shift was over. Total heaven! Sign up for the MAK Center’s newsletter to be alerted about next year’s event.

Tribune Magazine wrote about Reyner and his escape into the imaginary America, while The Guardian wondered what he would think of a more contemporary version of Los Angeles.

**

For my LA-dwellers: jump in the car! Don’t you want to tell Los Angeles how much you love her?

Kelsey

Thanks for writing this! My time in LA was as deeply formative to me as an urbanist as it was to you as an architectural historian. Banham's work so vividly describes how the city's form, its open and eccentric culture, and its gloriously inventive architectures are three parts of a whole that define the place. This post does something of the same. Well done!