The Museum of Drawers: famous artists collaborating in miniature

Creativity blooms best when it's shared with your friends.

❥ This email may be truncated in your inbox. To make sure you are reading the entire post, please move yourself along to a web browser!

All photographs and words here are my own, unless otherwise stated. More from me + Absolument can be found in these places:

Website | Instagram | Shop Absolument | Book Recs - Merci, thank you tons and tons for reading!

A Life in Museums

Between college degrees, I moved to New York City for a summer, hoping that I could make it a place to settle for an extended amount of time. Truly, living in that city had been a dream since I was tiny. My entire identity eventually became focused on art, and I was entranced with the modern era.

I completed my Art History program, plotted the stint in NYC, and planned to finish my second degree in Museum Studies afterward. For those few months in America’s most grand city, I filled every blip of time with art. I worked full-time as a project archivist for PACE Gallery Monday through Thursday, interned in the publications department at MoMA PS1 on Fridays and Saturdays, and volunteered in the education department at MoMA on Sundays. This 65-ish-hour work schedule and all its teachings imprinted themselves on me (and I can confidently say that I wouldn’t be able to manage that kind of energy today)!

During my lunch breaks or on the walk to the metro toward my apartment in Greenpoint, I made frequent detours to other museums or finally sneaked over to different gallery spaces in MoMA. Free museum entry tasted sweet. I made sure to soak up the pieces I had only seen in books, online, and in class. At MoMA, it was paintings like Dalí’s The Persistence of Memory, Van Gogh’s The Starry Night, Jackson Pollock’s One: Number 31, 1950.

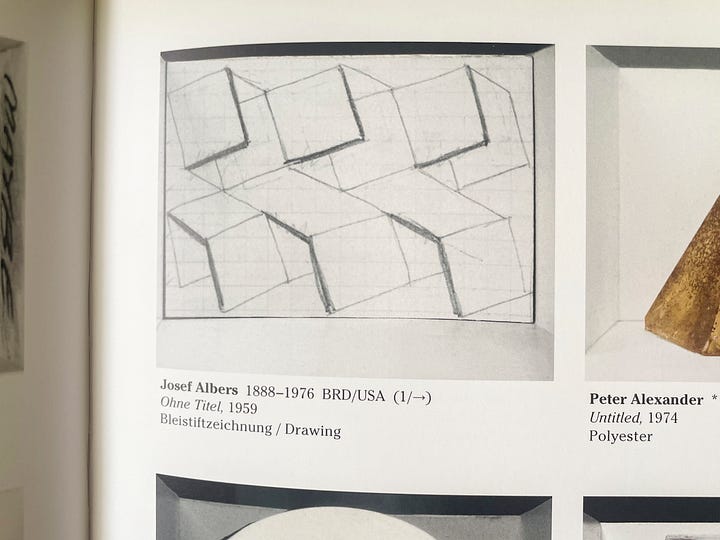

My days at MoMA PS1 were spent talking to people about art books, cleaning up their bookstore, and learning whatever I could. At the end of the summer, my boss offered me two free books from the store. Whatever I’d like! I had my answer quickly: a Josef Albers catalog from a just-exhibited retrospective at Galleria Civica di Modena and a mysterious book that I had been eyeing all summer, The Museum of Drawers.

That summer was thirteen years ago—somehow!

This month, I’ve been putting together a few exciting Substack collaborations with friends and strangers-turned-friends. It’s reminding me so much of that time in New York and the Museum of Drawers project. So, I’m welcoming April by sharing this art-related collaboration and kicking off these fulfilling writings with friends.

Hello, April, hello friends!

The Museum of Drawers

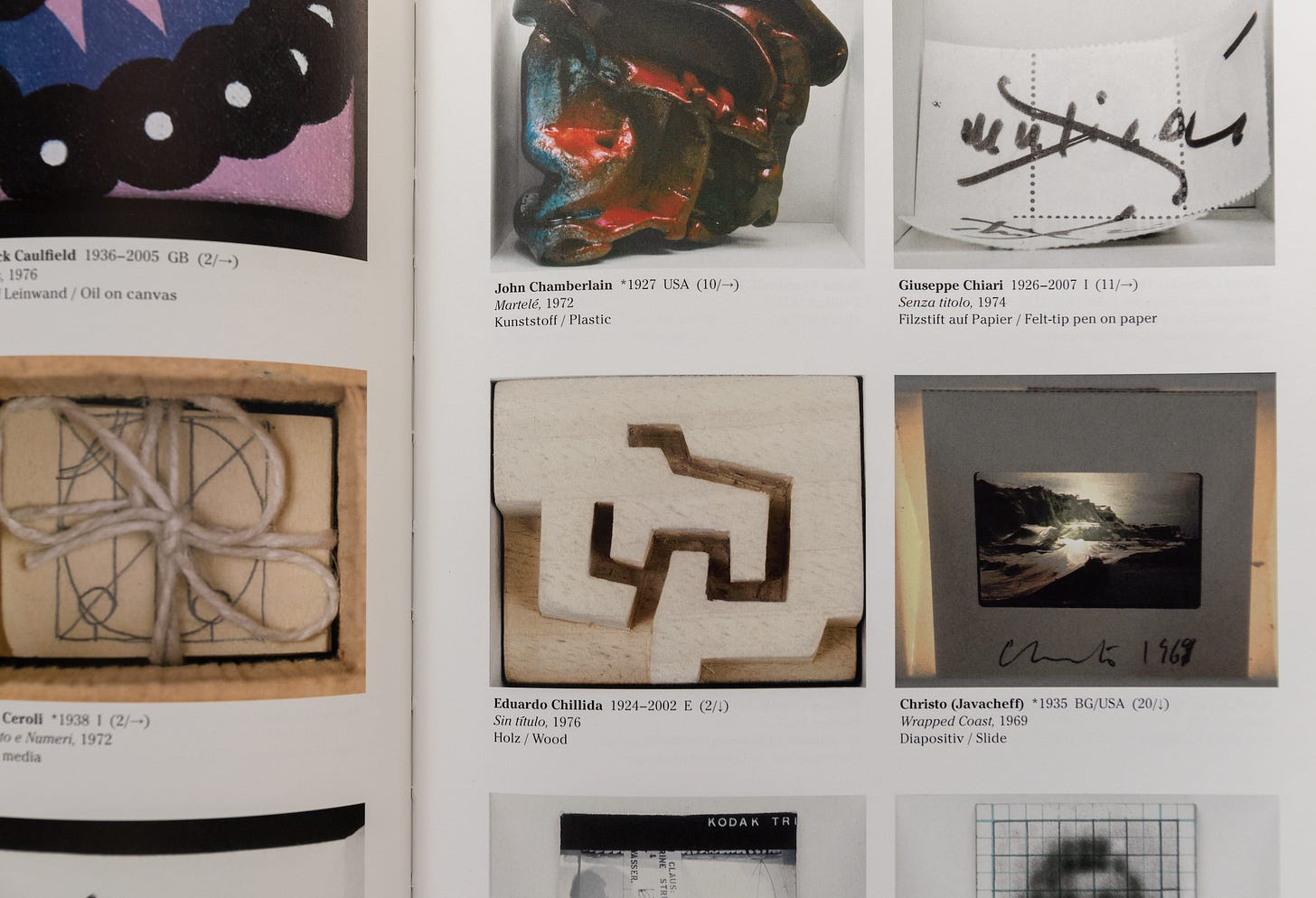

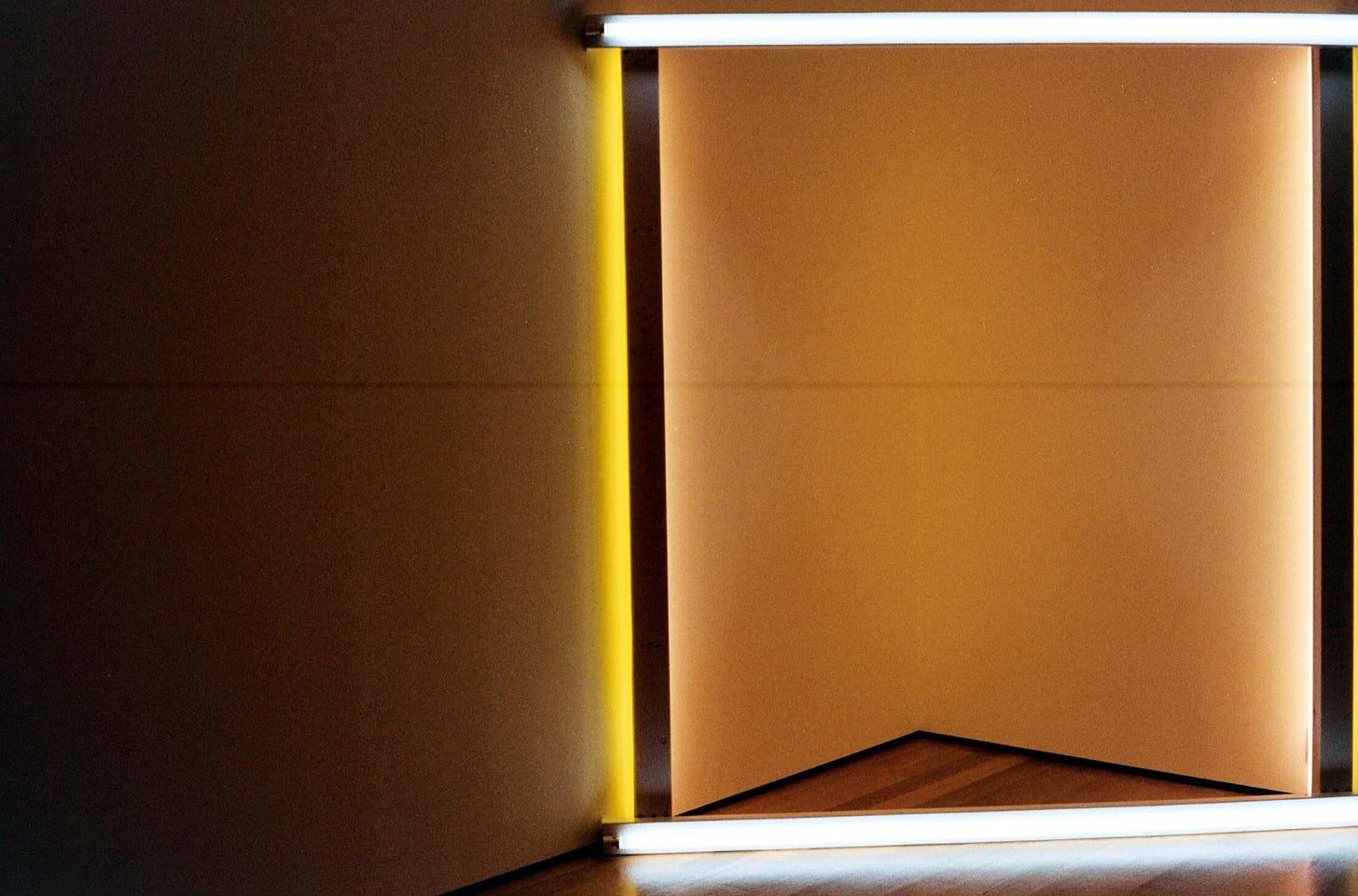

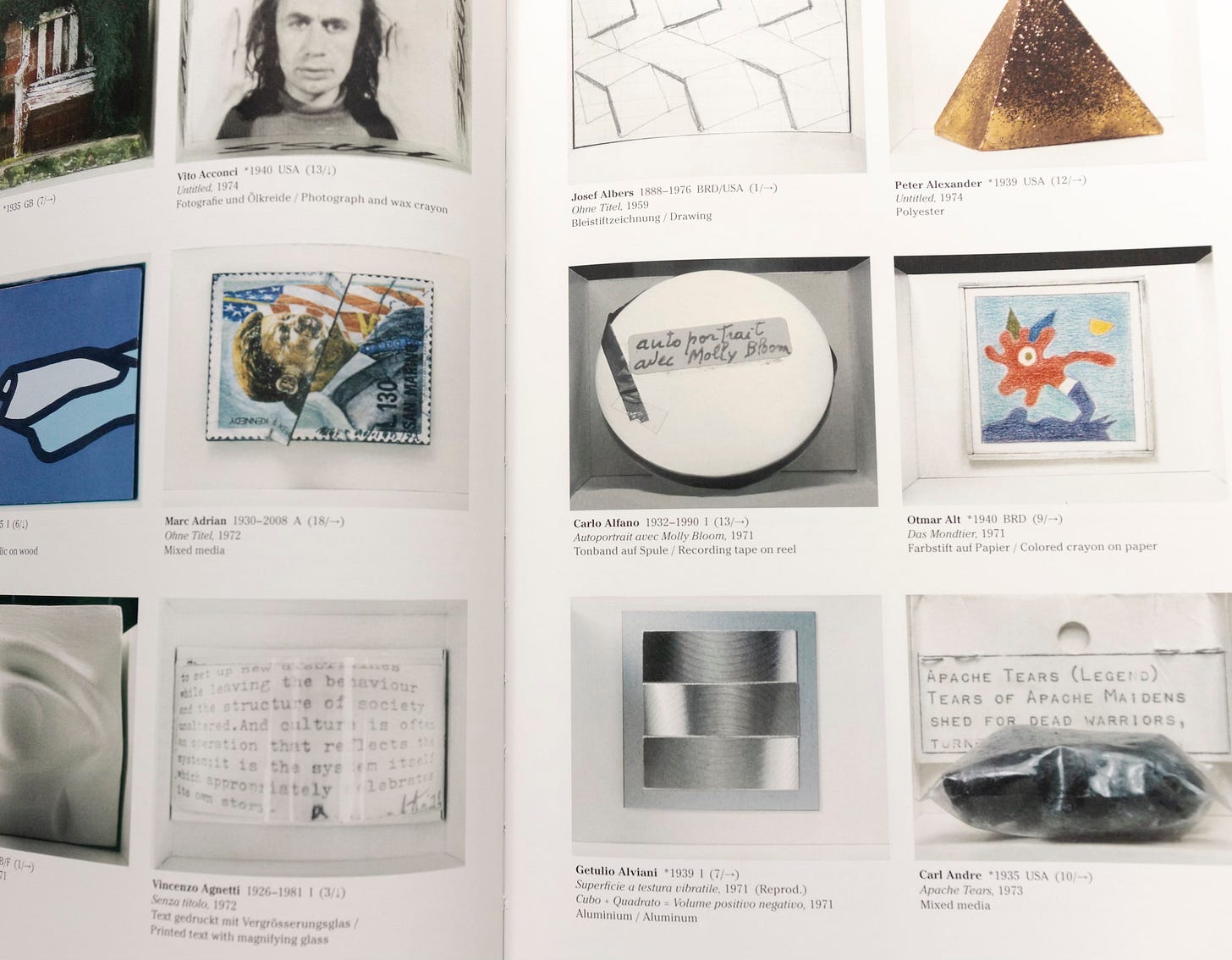

The Museum of Drawers is a unique, curatorial art experiment begun in 1970 by Herbert Distel. In its form, it’s a twenty-story haberdashery storage cabinet that Distel transformed into a miniature museum containing 500 original works of art by 508 artists. The Schubladenmuseum created the publication about the project and now has a dizzyingly-perfect, immersive digital catalog for us to explore.

Herbert Distel explained its origins:

“While preparing for an exhibition at a gallery in Brussels in 1969, I came acoss an old box that a haberdashery store was throwing out. Although originally made to hold reels of sewing silk, it was not full of nails, screws, hooks, and other bits and pieces. The gallerist couldn’t bear to part with such a practical piece of furniture, despite my best efforts to persuade him otherwise. And I myself was so fascinated by this twenty-story skyscraper in miniature that as soon as I got back to Switzerland, I immediately called Gütermann’s Nähseide in Zurich to ask whether they had such a box to spare. Two or three months later, this wonderful object was in my studio.

It was almost certainly Marcel Duchamp’s Boîte-en-valise, a work I had first caught a glimpse of in London in 1966, which set in motion the spiral of thoughts and ideas that eventually led to the Museum of Drawers. In the second half of 1970, therefore, I began drafting and dispatching letters to a few select artists. My vision of using the box to generate a mosaic-like, multidimensional snapshot of the age—the vibrant and inspiring sixties!—was a very vivid one. It was to be a kind of compression of time.”

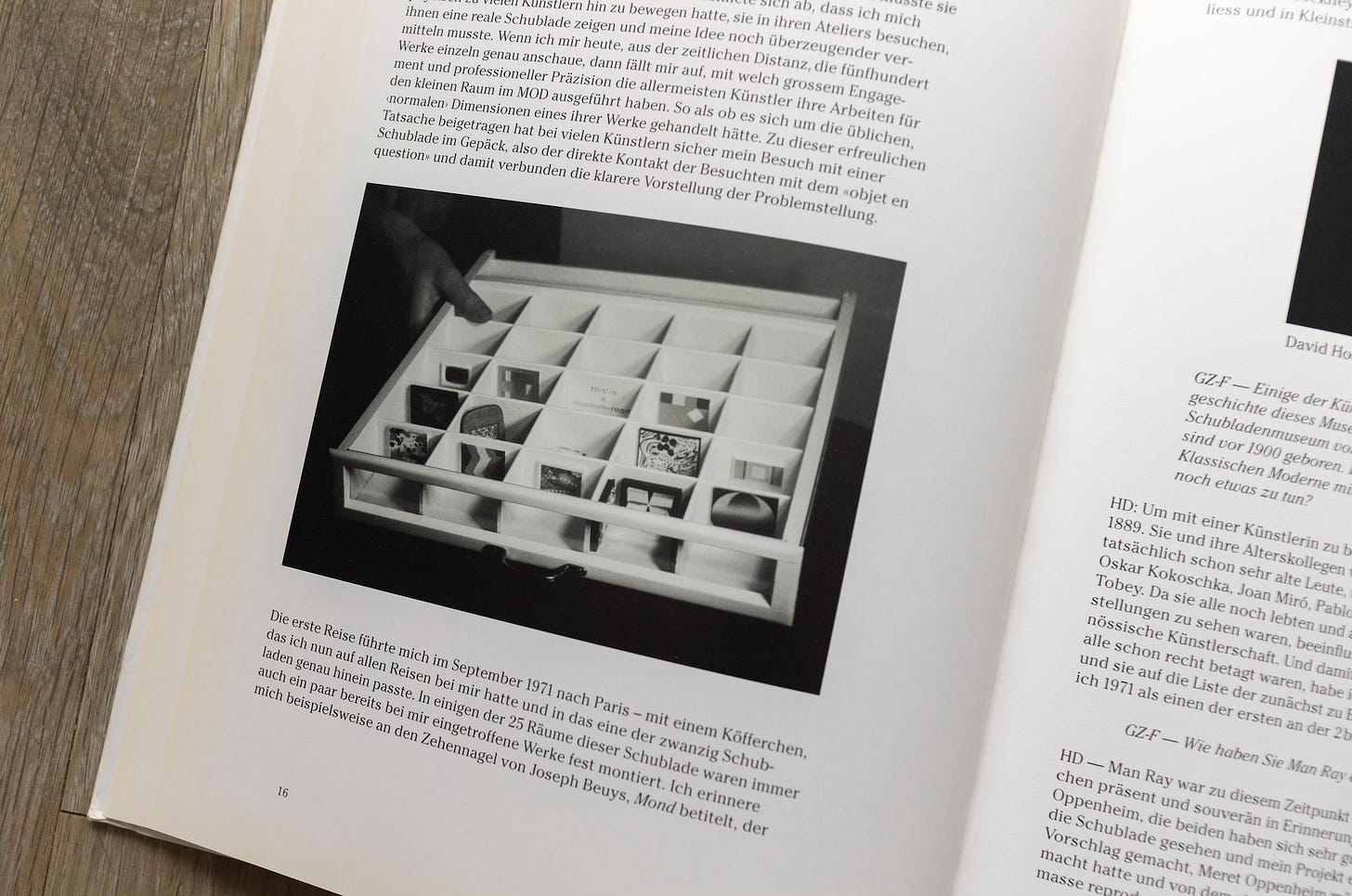

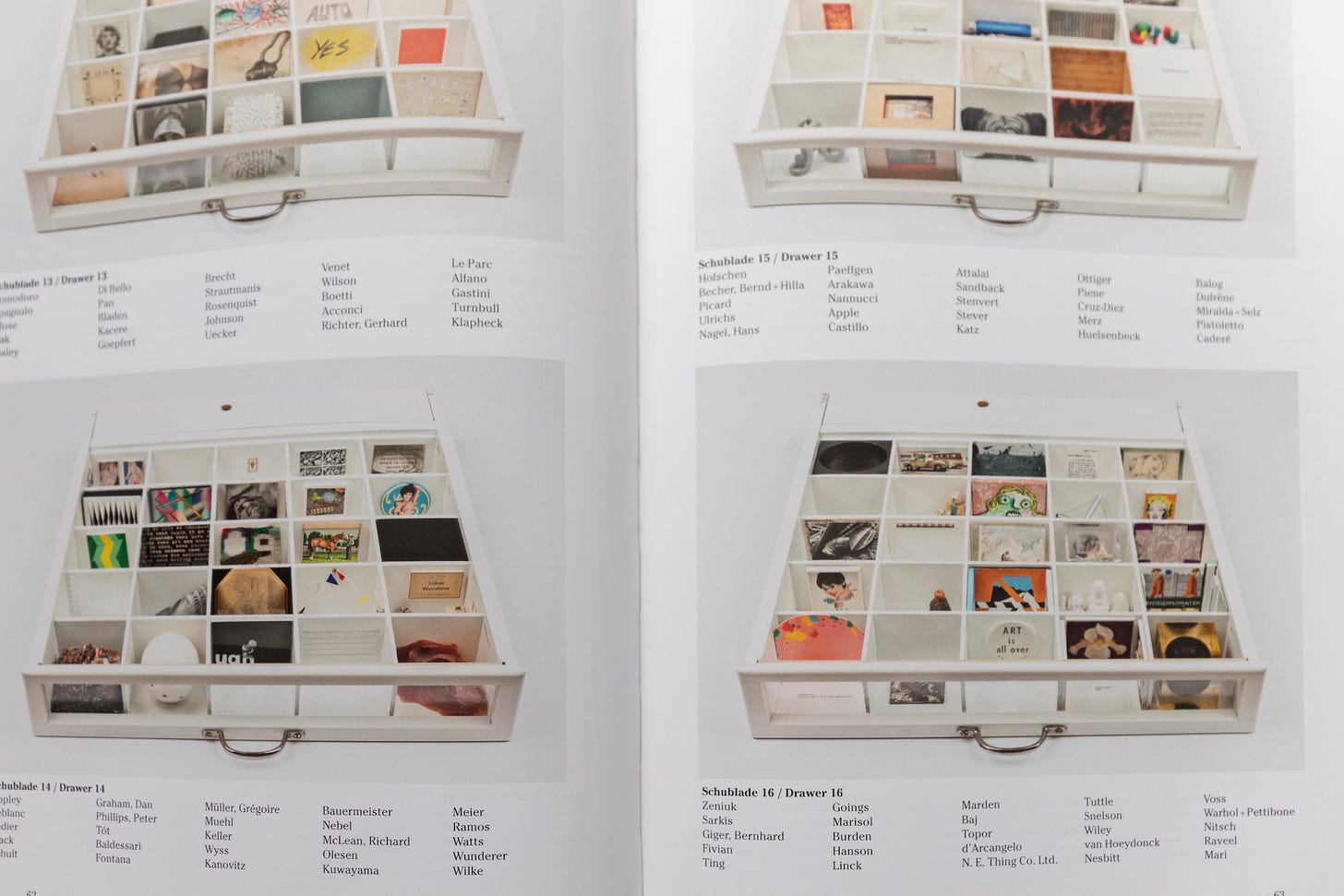

The idea was to give a miniature gallery room to each artist—filling 500 spaces measuring 1 11/16 x 2 1/2 x 1 7/8 inches each. To give Distel some credibility when trying to entice artists to participate (and for galleries to willingly share the mailing addresses of the aritsts), the finished project was scheduled to be on display at documenta 5 in 1972.

He first contacted the more famous artists, thinking that if they said yes, this was an absolute GO, GO, GO! On the primary list were Joseph Beuys, Meret Oppenheim, Hans Richter, and a dozen others. “To my great delight,” Distel said, “I had a positive response rate of 100 percent, and soon afterward began receiving the first tiny original artworks.”

As the project expanded, the drawers found themselves beautifully and creatively occupied. Some rooms, shockingly, were left void by Marcel Duchamp, Robert Irwin, Luciano Fabro, Barry Flanagan, Billy Apple, Marinus Boezem, Michelangelo Pistoletto, and Ian Wilson. Ditsel admired this empty flair. “Perhaps it would be worth taking these eight compartments as an example to show just how different content can be when emptiness is the theme.”

Marcel Duchamp died in 1968, two years before the project began, meaning that his drawer was left empty as a posthumous ode to the inventive oeuvre. “If you regard Marcel Duchamp with his idea of readymades as the one who basically unhinged the art world between 1914 and 1919, and who in doing so laid the groundwork for the currents of the 1960s and ‘70s such as Nouveau Réalisme, Fluxus, Pop Art, and Conceptual Art, then it is not hard to be reminded here of what came after, of the ‘anything goes’ paradigm and the notion that ‘everyone’s an artist’ that shaped Postmodernism….and [Duchamp’s] last great work certainly taught us a lesson—an impressive lesson in perception that reaches far beyond itself.” Further, Duchamp’s widow influenced Distel: “Marcel would undoubtedly have bagged a compartment for himself and then left it empty.”

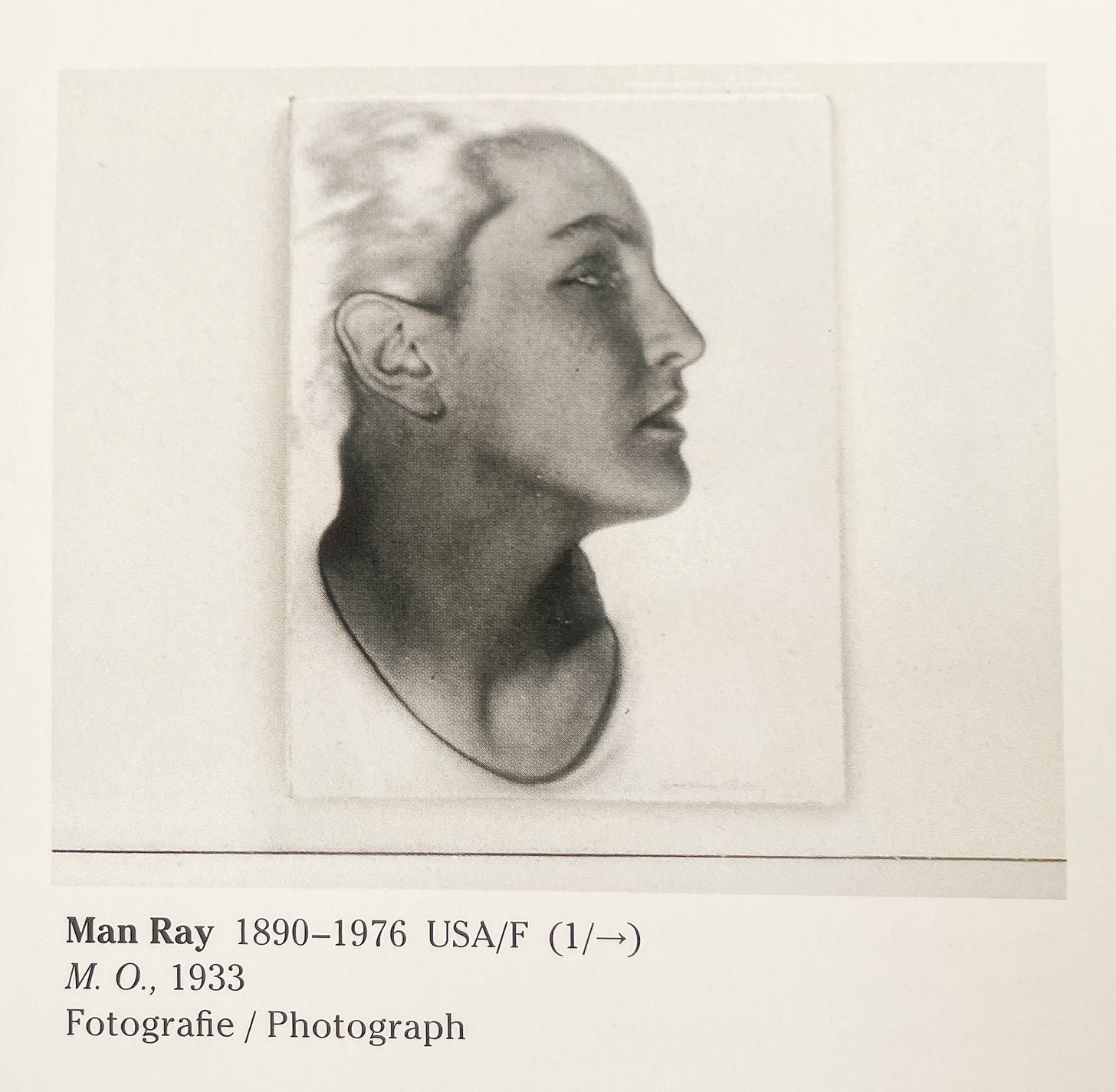

One piece that struck me was Man Ray’s. He was at the time one of the oldest artists who contributed and definitely one of the most prolific. He submitted a tiny photograph that he had taken of Meret Oppenheim in 1933. It’s the oldest work in the drawers.

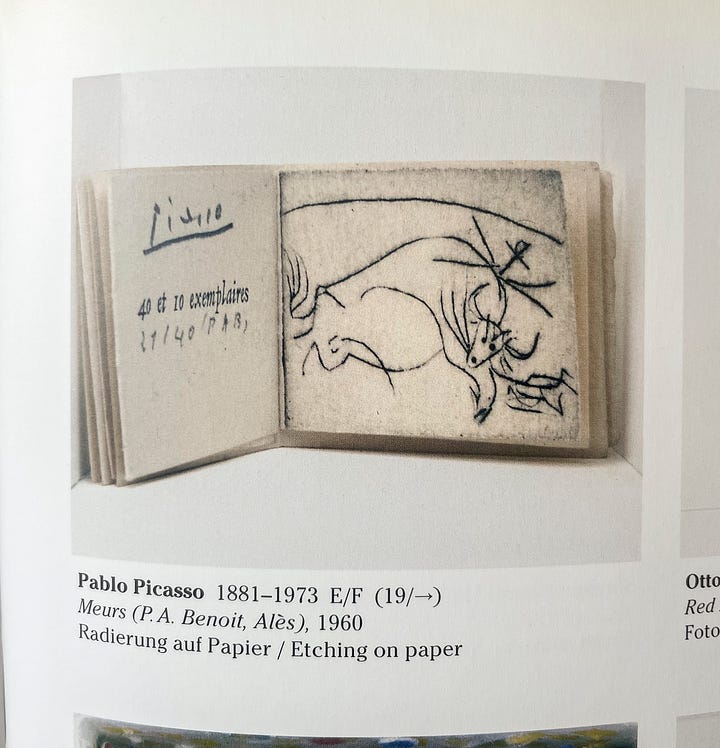

Some artists made commitments to the MOD, but passed away before they could start and/or finish their contribution. Distel speaks of his excitement to meet Picasso, but Pablo died two weeks before their meeting. Picasso’s art dealer and collector, Lynn Epsteen, knew of the MOD and Picasso’s willingness to join, and made sure something of his made it into his small, rectangular room. Josef Albers—one of my favorite artists—missed out just before passing away, but a trusted person made sure his gallery was accounted for.

Another shocking MOD story was Joseph Beuys, who sent his toenail, a little sculpture he titled Mond. It took him three months to grow it to the correct length. Despite the toenail sculpture, the only collaboration that Distel “rejected” from the Museum of Drawers was Salvador Dalí’s. Unsurprising! The Surrealist artist wanted the MOD to be permanently installed in his dome-shaped museum in Figueras, Spain. If Distel said no, there would be no miniature Dalí compartment.

The “skyscraper” took seven years to properly fill with scaled art, bringing him to several countries and dozens of artist studios. “The padded envelopes and little parcels trickled in steadily, filling up my post box at the main post office in Bern. It was a bit like one long-drawn-out Christmas.”

Distel shared more about the positive outcome:

“[The artists] are just people like you and me after all. What they all have in common, perhaps, is their curiosity; artists generally tend to be curious by nature. I certainly am. This curiosity can be brought to bear on all kinds of things, but in most cases, on the artist’s own work. And that was probably the element linking them together. I was very excited about being able to meet so many of these artists in person and to see them at work in their studios. There was this desire to understand what it is that drives, or moves, each individual. In this respect, the artists were as heterogeneous as their works; completely different worlds came to light, especially in their perception of others.”

Invite your friends to read Absolument ! and receive a “paid” subscription for free.

When you use the referral link below or the “Share” button on any of my posts, you'll get credit for any new subscribers. Simply send the link in a text, email, or share it on social media with friends.

3 friend referrals gets you 1 month free access to all posts

6 friend referrals gets you 3 months free access to all posts

25 friend referrals gets you half of a year free access to all posts

Collaborations incoming this month!

A Three Pots of Inspiration filled with sharings from three women whose creative and visual worlds I admire.

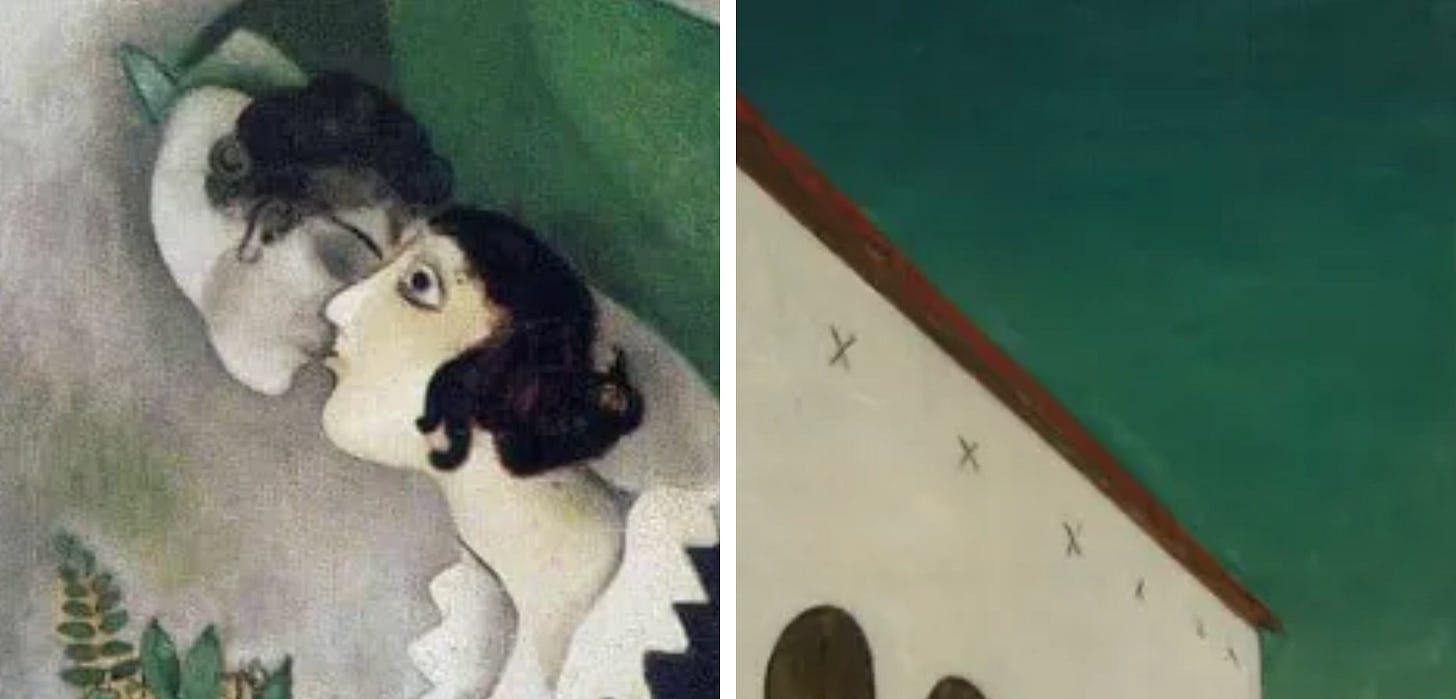

A thrilling little writing experiment that 15 people (myself included) have enthusiastically agreed to challenge themselves by authoring some fictional stories about art. They were assigned one of two modern paintings that I pre-selected with the same guidelines to follow. The short stories are slowly revealing themselves as the deadline approaches. I can’t wait for you all to read them soon!

**

How would you fill your museum drawer?

Kelsey Rose

The Museum of Drawers is absolutely fascinating—thank you for bringing this to my attention! I love the idea of each artist having their own miniature gallery in a drawer, and the way that the Schubladenmuseum has digitized the MOD is really astonishing.

As someone who was obsessed with all things miniature as a child, this is unbelievably cool to both 8 and 28 year old me.