Impressionism's sharp break from tradition

❥ Absolument's Dictionary of Modern Art - Spending springtime learning about modern artists and art movements, together.

❥ This email may be truncated in your inbox. To make sure you are reading the entire post, please move yourself along to a web browser!

More from me + Absolument can be found in these places: Website | Instagram | Shop Absolument | Book Recs

If you enjoy this writing and imagery, would you mind liking, commenting, or sharing it with a friend?

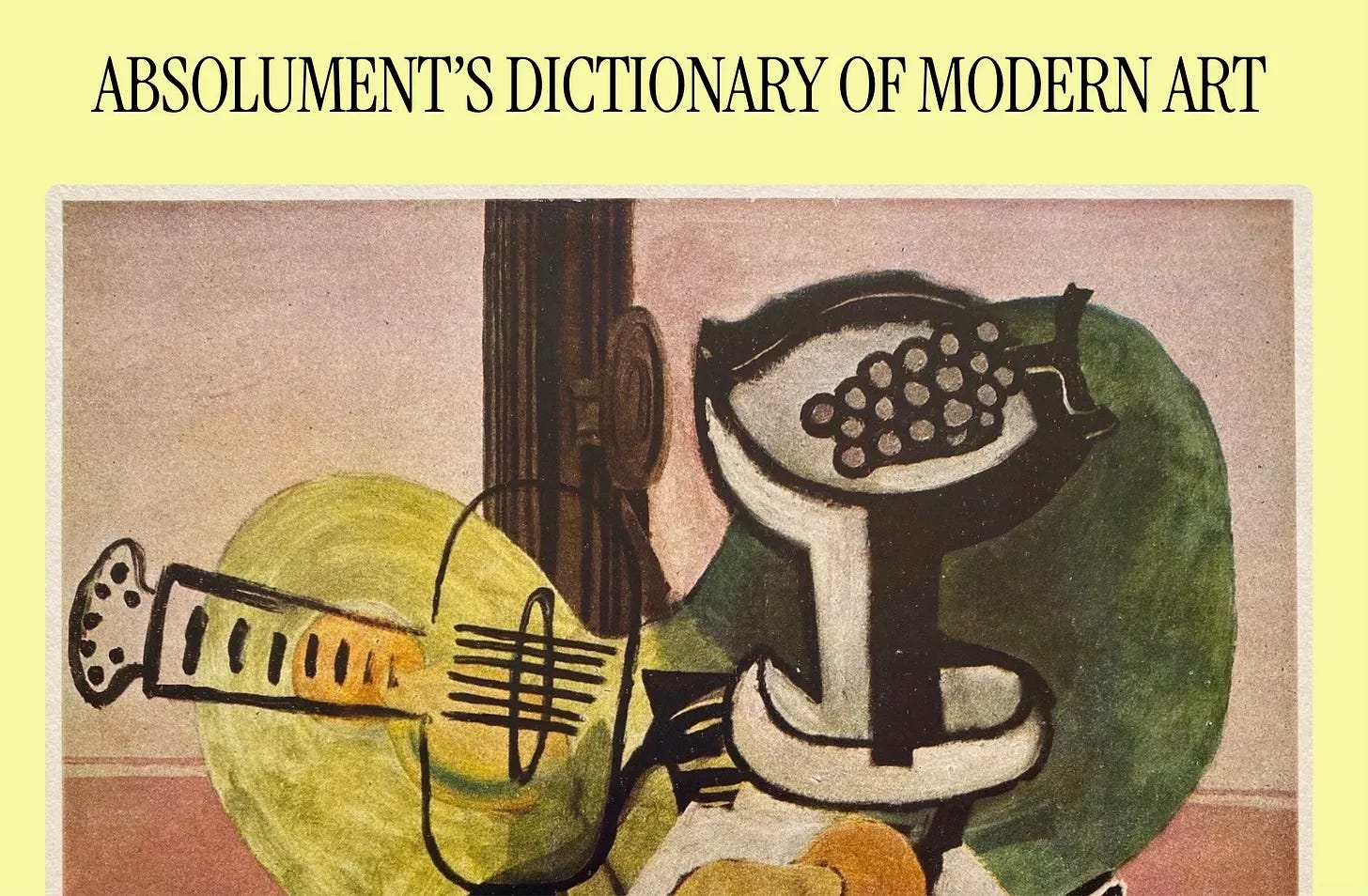

Georges Braque's "La Guitare Et Le Compotier," 1940 is perfectly situated on the cover of Absolument’s Dictionary of Modern Art.Twice a week from February through May, I’ll be sharing a supplementary newsletter for my paid subscribers: Absolument’s Dictionary of Modern Art. Each writing will focus on an artist or movement from the modern era, mimicking entries of a dictionary or encyclopedia.

You can read more about the series in this introductory newsletter.

Will you join me in learning about modern artists? I hope you will!

Visit THE INDEX to see previous artists—and a preview of what’s to come:

Why the modern era?

There are three strong points that have pulled me effortlessly into the world of modern era art history:

The artists themselves, who lived such richly vibrant lives—and not even in a clichéd way! They have a magnifying glass on the world in ways that others didn’t.

The ability for these people to break the rules and deny social conventions. To say no to their governments, institutions, and the people dictating what they can and cannot do. In the realm of painting/sculpture/other media, but also in a political and social way. I admire it.

The era encompasses an incredible number of movements and styles. One modernist is not always like another. Impressionism! Pop art! Land art! Minimalism! Die Brücke! Abstract Expressionism! Really, there are no dull moments between 1860 and 1970.

Impressionism was truly the beginning of modern art

b. approximately 1867 in Paris | d. 1886 (Is there really a “death” date for Impressionism?)

Impressionism challenged tradition and political power of its time mainly by rejecting the control of the academic art system. Especially institutions like the Salon de Paris, which outlined the standards for “serious” art. The Impressionists’ loose brushwork and visible technique openly defied academic rules about beauty and what was considered a clean, finished work of art. This group of artists were our first rule breakers. Sotheby’s called their first show “an exhibition of rejects.”

Instead of polished historical or political scenes favored by the state, Impressionist artists focused on their quotidian lives. Painters stippled and colorized cafés, streets, leisure, and landscapes—all subjects considered trivial. The people of Paris (and across the world) didn’t share the Impressionists’ belief that a daily slice of bread, a walk to work, or time spent near a lake was beautiful enough to be immortalized.