“I want to dip my eyes into Gio Ponti imagery soup for the rest of my days,” I told someone dear to me after attempting to describe how meaningful this Italian designer’s oeuvre seemed. This phrase remains my only way of properly summarizing how I feel about Gio Ponti, and I think showing photographs of his Villa Planchart design will help illustrate my point. Quickly, you’ll be asking if your eyes can be an ingredient in his special soup too.

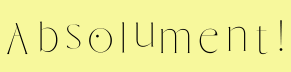

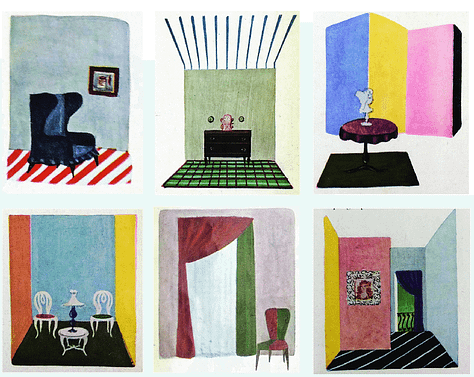

Giovanni “Gio” Ponti’s creative output spanned sixty years. Sixty years! That’s almost 22,000 days of this man having ideas, colors, textures, patterns, words swirling in his mind. From these concept-defining stretches and bouts of creativity, he transformed himself into an architect, interior designer, magazine founder and editor, inventor, writer, decorative artist, poet, furniture maker, and educator. He sent an unfathomable amount of letters to others, often dashed with spurts of color. His mental and physical worlds were undeniably varied.

Ponti’s architecture was a scaled-up version of his other avenues of work. I like to imagine him throwing one of his drawings up toward the sky and watching a perfectly intact building fall onto Earth moments later. (If only architecture worked that way!) One of my favorite projects of his, Villa Planchart, was constructed between 1953 and 1957 for husband-and-wife Armando and Anala Planchart, avid readers of Ponti’s Domus magazine.

A majority of Gio’s design presence naturally involved Italy, however, this project for the Plancharts settled itself rather neatly in Caracas, Venezuela. Despite the difference in scenery, culture, and building restrictions, Ponti’s Italian* pizzazz was easily transported to this site’s lush hill. Ponti fantasized about creating a home “as graceful as a butterfly.” Successfully building this residence took over 700 pieces of correspondence with the Plancharts and what he described as “a very pleasant task because the requests were always intelligent, clear, discrete, made with trusting friendship.”

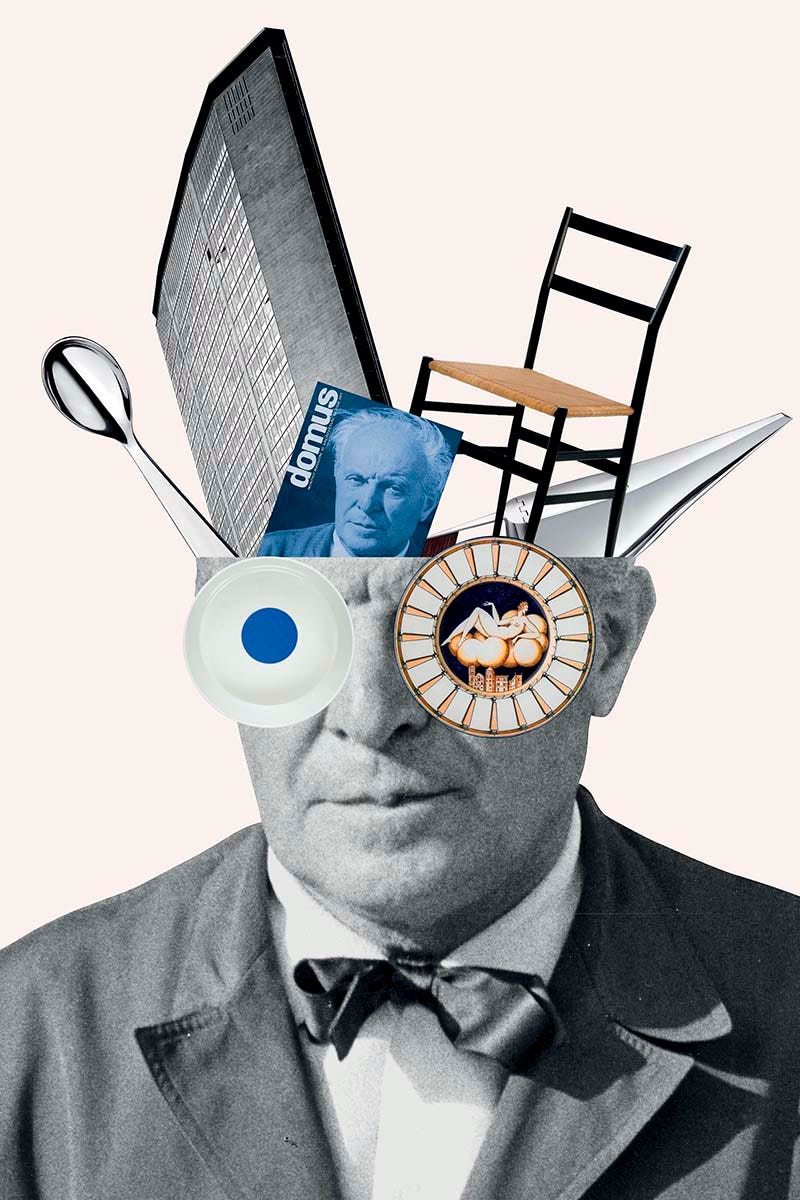

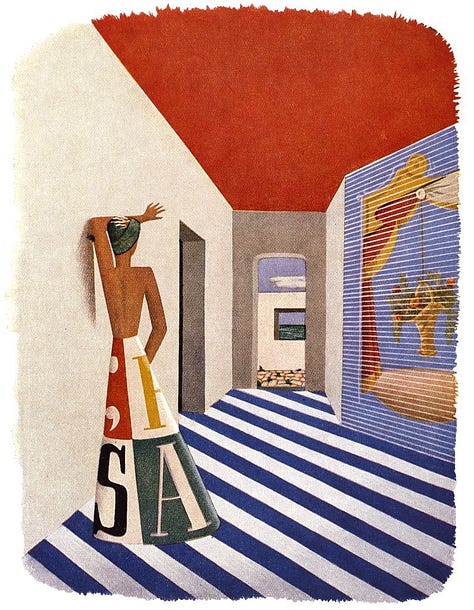

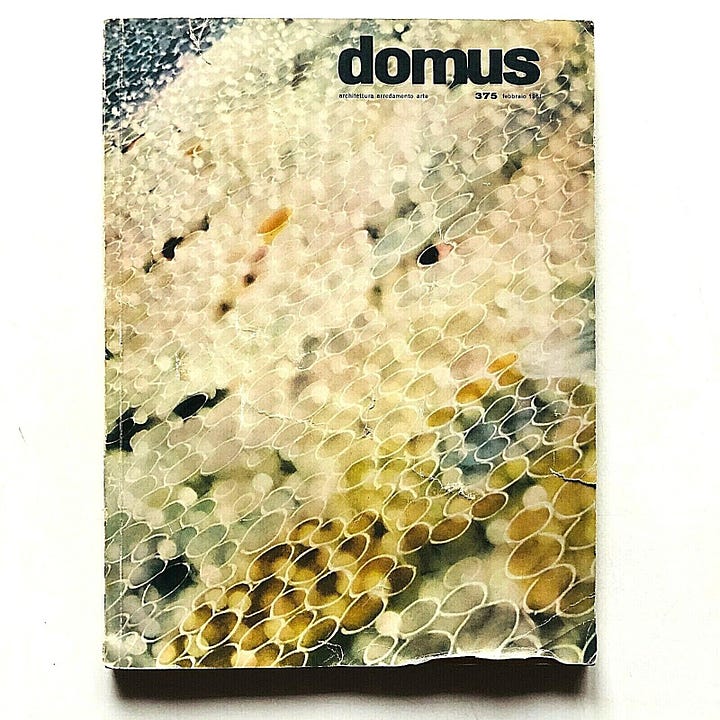

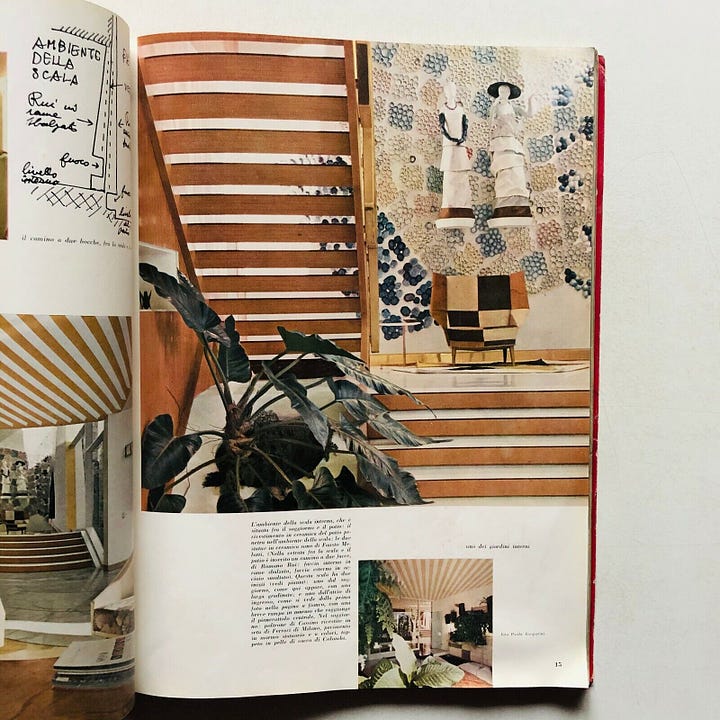

Ponti wrote about the design in his magazine Domus in February 1961, revealing its “seven perspective views crossing the body of the house” and characterizing it as “a game of spaces, surfaces, and volumes offered in different ways to those who visit.” He overcame quite the task of making cement, marble, and other substantial building materials appear nimble and buoyant. Yellow and white-striped ceilings within the main hall provided directed movement, punctuated by a meeting with vastly different materials, textures, and series of colors. There is a noticeable absence of doors, except in places where the law required them.

As unusual as Villa Planchart was, the design did follow some modern-era conventions: a people-centric approach, a focus on the inherent strength of materials, a new fluidity of space, and the presence of greenery and sunlight within the home—as if there were no delineation between the inside and outside. “But this building is not made only for the eye; it is made for the life of its inhabitants,” Ponti remarked. “With careful understanding, it accentuated what was requested, receiving, in the end, the truest praise for the architect: the affirmation that he succeeded in providing what was desired, and requested, for the life of the residents.”

What you see in this residence—the realization of Ponti’s mind’s eye and the depths of his understanding of space, hues, and materials—it’s a ladle of his soup.

***

*Gio Ponti commented that he didn’t intend to build an “Italian” design, but because of his “Italian-ness”, this residence was “unconsciously, but happily, part of one's own country”:

The other is that, having acted only with sincerity without any 'Italian' preconditioning, that is, without wanting to create, as Cocteau put it, une architecture (italienne) d'après l'architecture (italienne), the surprising episode (and dear to me) came about in which I said that this was a "Florentine villa." This opinion, delivered with sincerity spontaneously by local residents, apart from any pretense of expressing any opinion about "architecture," is probative of one thing: that is even when making an architecture that unscrupulously results from its own time, one is (or remains) unconsciously, but happily, part of one's own country; that is Italian, more in the deep and true tradition and not in a formal and academic way. It is neither necessary to be a dogmatic follower of modern design or a dogmatic follower of traditional design to be modern and traditional, nor even to be preoccupied with all of this. It is enough to know the spirit of a modern culture and, as far as 'Italian-ness' is concerned, it is enough just to be Italian. Thus, as an Italian, I was able to pay tribute to Venezuelan citizens who honored me be calling upon me to work in their beautiful capital.

***

Extra notes:

Read more of Ponti’s own thoughts about Villa Planchart from Domus issue 375, February 1961.

Speaking of DOMUS—it’s still in publication. You can subscribe to the magazine here, or there is a book series that highlights the decades of the magazine’s output. I especially want to flip through the edition that covers the years 1928-1939.

There was a Ponti exhibition at the Musée des Arts Décoratifs in Paris in 2018. Here’s a great interview in Domus with the museum director/curator of the show, Olivier Gabet.

I often find myself relating architects/designers and their creations to food, so this won’t be the last connection you see like this here. I’m hungry in too many ways.

Bon appétit—I mean…merci !

Kelsey